Introduction

As late as 1970, Sudan boasted some of the most

unspoilt and isolated wilderness in east Africa,

and its wildlife populations were world-renowned.

While the past few decades have witnessed a major

assault on both wildlife and their habitats, what

remains is both internationally significant and an

important resource opportunity for Sudan.

Ecosystems, issues, and the institutional structures

to manage wildlife and protected areas differ

markedly between north and south in Sudan. In

the north, the greatest damage has been inflicted

by habitat degradation, while in the south, it is

uncontrolled hunting that has decimated wildlife

populations. Many of the issues in the following

sections are hence addressed separately for the

two areas of the country. It should be noted

that the most important remaining wildlife and

protected areas in northern Sudan are on the

coastline or in the Red Sea; these are covered in

Chapter 12.

This chapter focuses on wildlife and protected

areas as a specific sector. It is acknowledged that

the larger topic of biodiversity has not been

adequately addressed in this assessment. While

the importance of conserving biodiversity is

unquestionable, a significant difficulty for action

on this front – in Sudan as elsewhere – is the lack

of government ownership: no single ministry is

responsible for this topic. As a result, the observed

implementation of recommendations under the

label of biodiversity is poor.

Although it has not been included as a specific sector

in this assessment, the biodiversity of Sudan was

studied and reported on in 2003 by a programme

funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF)

under the auspices of the Convention on Biological

Diversity (CBD) [11.1].

Assessment activities

The investigation of issues related to wildlife and

protected areas in Sudan was conducted as part

of the overall assessment. Two commissioned

desk studies – one by the Boma Wildlife Training

Centre, the other by the Sudanese Environment

Conservation Society (SECS) – summarized

the extent of existing knowledge for the south

and north respectively [11.2, 11.3]. UNEP was

able to visit one major site in the north (Dinder

National Park), as well as a number of smaller

reserves. The protected areas of Southern Sudan

and Darfur were inaccessible due to security and

logistical constraints. However, information

was obtained from interviews and other sources

in the course of general fieldwork in Southern

Sudan.

Due to historical and ongoing conflicts, the

available data on wildlife is highly skewed, with

most recent information limited to northern and

central states. This lack of up to date field data is a

core problem for Southern Sudan’s protected areas,

but major studies by the Wildlife Conservation

Society are underway in 2007 to correct this.

11.2 Overview of the wildlife and

habitats of Sudan

The arid and semi-arid habitats of northern Sudan

have always had limited wildlife populations. In

the north, protected areas are mainly linked to the

Nile and its tributaries, and to the Red Sea coast,

where there are larger concentrations of wildlife.

In contrast, the savannah woodlands and flooded

grasslands of Southern Sudan have historically been

home to vast populations of mammals and birds,

especially migratory waterfowl. This abundance

of wildlife has led to the creation of numerous

national parks and game reserves by both British

colonial and independent Sudanese authorities.

There is a large volume of literature on the wildlife of

Sudan as recorded by casual observers who travelled

through or lived in Sudan during the 19th and first

half of the 20th centuries. A 1940s account, for

instance, describes large populations of elephant,

giraffe, giant eland, and both white and black rhino

across a wide belt of Southern Sudan. Because of the

civil war, however, few scientific studies of Sudan’s

wildlife have been conducted, and coverage of the

south has always been very limited.

The management of migratory wildlife outside of protected areas:

the white-eared kob

One of the distinctive features of the wildlife population of Southern Sudan is that much of it is found outside of protected areas. This

presents a range of challenges for conservation and management, as illustrated by the case of the white-eared kob antelope.

White-eared kob (Kobus kob leucotis) are largely restricted to Southern Sudan, east of the Nile, and to south-west Ethiopia

[11.19, 11.20]. These antelope are dependent on a plentiful supply of lush vegetation and their splayed hooves enable

them to utilize seasonally inundated grasslands. The spectacular migration of immense herds of white-eared kob in search

of grazing and water has been compared to that of the ungulates in the Serengeti.

Substantial populations of white-eared kob occur in Boma National Park, the Jonglei area and in Badingilo National Park

[11.20]. The paths of their migration vary from year to year, depending on distribution of rainfall and floods (see Figure

11.1). A survey and documentary film made in the early 1980s followed the herds of the Boma ecosystem as they moved

between their dry and wet season strongholds that year, and found that the herds moved up to 1,600 km per year, facing

a range of threats as they migrated through the different seasons, ecosystems and tribal regions [11.5].

The principle threats to the kob are seasonal drought, excessive hunting pressure and now the development of a new aidfunded

rural road network cutting across their migration routes. The sustainable solution to excessive hunting is considered

to be its containment and formalization rather than its outright prohibition, a measure which is both unachievable and

unenforceable. White-eared kob represent an ideal opportunity for sustainable harvesting: they have a vast habitat, are fast

breeders and are far better adapted to the harsh environment of the clay plains and wetlands than cattle. The spectacular

nature of the kob migration may support some wildlife tourism in future but it is unrealistic to expect tourism revenue to

provide an acceptable substitute for all of the livelihoods currently supported by hunting.

Minimizing the impact of the new road network will require some innovative thinking to integrate animal behaviour

considerations into road design and development controls. Dedicated wildlife-crossing corridors, culverting and underpasses

are all options that could reduce road accident-related animal deaths, while banning hunting within set distances of the

new roads may help to control vehicle-assisted poaching.

As a result of this lack of technical fieldwork,

virtually all up to date evidence of wildlife

distribution in Southern Sudan outside of a

few protected areas is anecdotal and cannot be

easily substantiated. Nonetheless, this type of

information is considered to warrant reporting

in order to assess priorities for more substantive

assessments. Key information from 2005 and 2006

includes the sightings of elephants in the northern

part of the Sudd wetlands, and the sighting of very

large herds of tiang and white-eared kob in Jonglei

state. It is of note that both of these sightings took

place outside of legally protected areas (see Case

Study 11.1).

The only other recent data available on Southern

Sudan is from ground surveys of Nimule, Boma

and Southern National Park, carried out by the

New Sudan Wildlife Conservation Organization

(NSWCO) in 2001. The results of these surveys

and other information provided to UNEP by

the Boma Wildlife Training Centre indicate that

many protected areas, in Southern Sudan at least,

have remnant populations of most species.

Figure 11.1 Kob migration

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Jonglei

Lakes

Eastern Equatoria

Bahr El Jabal

Upper Nile

Unity

Western Equatoria

Upper Nile

Bor Boma

Ayod

Waat

Yirol

Pibor

Lafon

Akobo

Nasser

Terakeka

Pochalla

ETHIOPIA

0 40 80 120 160 200

Kilometres

Legend

Kob migration

Rivers

International border

State border

Sources:

Approximate movements of Boma

population of white-eared kob in the

early 1980s.

Adapted from Survival Anglia 1984.

UNEP sightings - May 2006

©Andrew Morton

Tiang, Bokor reedbuck and white-eared kob near

the main road in Mabior, Jonglei state. Wildlife in

Southern Sudan are found as much outside as

inside protected areas

The regional environments of Sudan defined in

Chapter 2 can be used as a basis for the description

of current wildlife habitats and populations:

• arid regions (coastal and arid region mountain

ranges, coastal plain, stony plains and dune fields);

• the Nile riverine strip;

• the Sahel belt, including the central dryland

agricultural belt;

• the Marra plateau;

• the Nuba mountains;

• savannah;

• wetlands and floodplains;

• subtropical lowlands;

• the Imatong and Jebel Gumbiri mountain

ranges; and

• subtidal coastline and islands – covered in

Chapter 12.

The delimitations of the various areas in which

wildlife are present are derived from a combination

of ecological, socio-economic, historical and

political factors. It should be noted, however,

that the boundaries between certain regions are

ill-defined, and that many animals migrate freely

across them.

Arid regions. The mountains bordering the Red

Sea, as well as those on the Ethiopian border

and in Northern Darfur, are host to isolated

low density populations of Nubian ibex, wild

sheep and several species of gazelle [11.3]. Larger

predators are limited to jackal and leopard. Due

to the lack of water, wildlife in the desert plains

are extremely limited, consisting principally of

Dorcas gazelle and smaller animals. Life centres on

wadis and oases, which are commonly occupied

by nomadic pastoralists and their livestock.

The Nile riverine strip. The Nile riverine strip

is heavily populated and as such only supports

birdlife and smaller animals (including bats).

The Sahel belt, including the central dryland

agricultural belt. In the Sahel belt, the

combination of agricultural development and

roving pastoralists effectively excludes large

wildlife, although the region does host migratory

birds, particularly in the seasonal wetlands and

irrigated areas. With the important exception

of Dinder National Park, the expansion of

mechanized agriculture has eliminated much of

the wild habitat in the Sahel belt.

The Marra plateau. The forests of Jebel Marra

historically hosted significant populations of

wildlife, including lion and greater kudu [11.3].

Limited surveys in 1998 (the latest available)

reported high levels of poaching at that time. Due

to the conflict in Darfur, there is only negligible

information on the current status of wildlife in

this region.

The Nuba mountains. The wooded highlands

of the Nuba mountains historically held large

populations of wildlife, but all recent reports

indicate that the civil war led to a massive decline

in numbers and diversity, even though forest cover

is still substantial. The UNEP team travelled

extensively through the Nuba mountains without

any sightings or reports of wildlife.

Savannah. The bulk of the remaining wildlife of

Sudan is found in the savannah of central and

south Sudan, though the data on wildlife density

in these regions is negligible.

Historical reports include large-scale populations of

white and black rhino, zebra, numerous antelope

species, lion, and leopard. In addition, aerial surveys

carried out in the woodland savannah of Southern

National Park in November 1980 revealed sizeable

population estimates of elephant (15,404), buffalo

(75,826), hartebeest (14,906) and giraffe (2,097)

[11.4]. The number of white rhino in Southern

National Park was estimated to be 168, which

then represented a small but significant remnant

population of an extremely endangered subspecies

of rhino. In 1980, aerial surveys carried out in Boma

(mixed savannah and floodplain habitats) indicated

that the park was used by large populations of a

wide variety of species as a dry season refuge, with

the exception of the tiang, whose numbers increased

considerably during the wet season [11.5].

Wetlands and floodplains. The vast wetlands

and floodplains of south Sudan, which include

the Sudd and the Machar marshes, are an

internationally significant wildlife haven, particularly

for migratory waterfowl. These unique

habitats also support many species not seen or

found in large numbers outside of Sudan, such as

the Nile lechwe antelope, the shoebill stork and

the white-eared kob.

Subtropical lowlands. The subtropical lowlands

form the northern and western limits of the

central African rainforest belt and thus host

many subtropical closed forest species, such as

the chimpanzee.

The Imatong and Jebel Gumbiri mountain

ranges. The wetter microclimates of these

isolated mountains in the far south of Southern

Sudan support thick montane forest. There is

only negligible information available on wildlife

occurrences in these important ecosystems.

The flooded grasslands of Southern Sudan support very large bird populations, including black-crowned

cranes (Balearica pavonina) (top left), pink-backed pelicans (Pelecanus rufescens) (top right), cattle egrets

(Bubulcus ibis) (bottom left), and saddle-billed storks (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis) (bottom right), seen

near Padak in Jonglei state

Sudan harbours a number of globally important

and endangered species of mammals, birds,

reptiles and plants, as well as endemic species.

In addition, there are a number of species listed

as vulnerable by IUCN, including sixteen species

of mammals, birds and reptiles: hippopotamus

(Hippopotamus amphibius); cheetah (Acinonyx

jubatus); African lion (Panthera leo); Barbary

sheep (Ammotragus lervia); Dorcas gazelle (Gazella

dorcas); red-fronted gazelle (Gazella rufifrons);

Soemmerring’s gazelle (Gazella soemmerringei);

African elephant (Loxodonta africana); Trevor’s

free-tailed bat (Mops trevori); horn-skinned

bat (Eptesicus floweri); greater spotted eagle

(Aquila clanga); imperial eagle (Aquila heliaca);

houbara bustard (Chlamydotis undulata); lesser

kestrel (Falco naumanni); lappet-faced vulture

(Torgos tracheliotos); and African spurred tortoise

(Geochelone sulcata) [11.12 ].

The Mongalla gazelle is not endangered but has

a relatively small habitat. Rangeland burning such

as has recently occurred here is favourable to this

species, as it thrives on short new grass

Common name Scientific name Red List category

Mammals

Addax* Addax maculatus CR A2cd

African ass Equus africanus CR A1b

Dama gazelle Gazella dama CR A2cd

Nubian ibex Capra nubiana EN C2a

Grevy’s zebra* Equus grevyi EN A1a+2c

Rhim gazelle Gazella leptoceros EN C1+2a

African wild dog Lycaon pictus EN C2a(i)

Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes EN A3cd

Birds

Northern bald ibis Geronticus eremita CR C2a(ii)

Sociable lapwing Vanellus gregarius CR A3bc

Basra reed warbler Acrocephalus griseldis EN A2bc+3bc

Saker falcon Falco cherrug EN A2bcd+3b

Spotted ground-thrush Zoothera guttata EN C2a(i)

Reptiles

Hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata CR A1bd

Green turtle Chelonia mydas EN A2bd

Plants

Medemia argun Medemia argun CR B1+2c

Nubian dragon tree Dracaena ombet EN A1cd

CR = critically endangered; EN = endangered; * questionable occurrence in Sudan

Variable protection

A significant number of areas throughout Sudan

have been gazetted or listed as having some form

of legal protection by the British colonial or the

independent Sudanese authorities. In practice,

however, the level of protection afforded to these

areas has ranged from slight to negligible, and many

exist only on paper today. Moreover, many of the

previously protected or important areas are located in

regions affected by conflict and have hence suffered

from a long-term absence of the rule of law.

Protected areas of northern Sudan

According to the information available to UNEP,

northern Sudan has six actual or proposed marine

protected sites [11.13], with a total area of

approximately 1,900 km², and twenty-six actual or

proposed terrestrial and freshwater protected sites,

with a total area of approximately 157,000 km²

[11.1, 11.2, 11.14, 11.15, 11.16, 11.17].

أَلَمْ تَرَ أَنَّ اللَّهَ يُسَبِّحُ لَهُ مَنْ فِي السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالأرْضِ وَالطَّيْرُ صَافَّاتٍ كُلٌّ قَدْ عَلِمَ صَلاتَهُ وَتَسْبِيحَهُ وَاللَّهُ عَلِيمٌ بِمَا يَفْعَلُونَ Tidakkah kamu tahu bahwasanya Allah: kepada-Nya bertasbih apa yang di langit dan di bumi dan (juga) burung dengan mengembangkan sayapnya. Masing-masing telah mengetahui (cara) solat dan tasbihnya, dan Allah Amat Mengetahui apa yang mereka kerjakan. an-Nur:41

Tazkirah

Sami Yusuf_try not to cry

mu'allim Muhammad Rasulullah Sallallahu alaihi waSalam

ummi_mak_mother_ibu_Sami Yusuf

zikir Tok Guru Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat Mu'allimul Mursyidi

syeikh masyari afasi

ruang rindu

song

Arisu Rozah

Usia 40

Mudah mudahan diluaskan rezeki anugerah Allah

usia 40 tahun

UPM

Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

pemakaian serban semsa menunaikan solat_InsyaAllah ada sawaaban anugerah Allah

Rempuh halangan

Abah_menyokong kuat oengajian Ijazah UPM

usia 39 tahun

usia 23 tahun_UPM

An_Namiru

Ijazah Pengurusan Hutan UPM

General Lumber_Nik Mahmud Nik Hasan

Chengal

Tauliah

Semasa tugas dgn general lumber

PALAPES UPM

UPM

Rumah yang lawa

Muhammad_Abdullah CD

semasa bermukim di Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

Ijazah

air terjun

Borneo land

GREEN PEACE

GREEN PEACE

Kelang

Ahlul Bayti_ Sayid Alawi Al Maliki

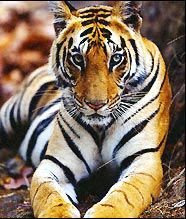

Asadu_ Tenang serta Berani

atTiflatul Falasthiniin

Sayid Muhammad Ahlul Bayt keturunan Rasulullah

AnNamiru_SAFARI_Kembara

AnNamiru_resting

Hamas

sabaha anNamiru fil nahri

Namir sedang membersih

Tok Guru Mualimul_Mursyid

An_Namiru

.jpg)

Namir_istirehat

.jpg)

SaaRa AnNamiru fil_Midan

.jpg)

Renungan Sang Harimau_Sabaha AnNamiru

.jpg)

Syaraba AnNamiru Ma_A

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNimru ma_A waladuha

Namir fil_Ghabi (sebut Robi...

Namir

AdDubbu_Beruang di hutan

Amu Syahidan Wa La Tuba lil_A'duwwi

AsSyahid

Namir

Tangkas

najwa dan irah

sungai

najwa

najwa

Kaabatul musyarrafah

unta

Jabal Rahmah

masjid nabawi

masjid quba

dr.eg

najwa dan hadhirah

along[macho]

![along[macho]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjuMi7D33CmR0_KXrCW2XigfLcUuQurcvtqOS139ncCwEzCyB-jUopk7QK7anADIenJEm2S0N6gAY1ubnACYXewgiAsI3rBjnLTawM39alLL-rEopOoVqn0w5WpLhPJH3hrXNtchEhgtyaI/s240/P7150023.JPG)

harissa dan hadhirah

adik beradik

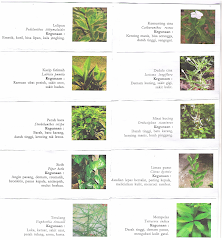

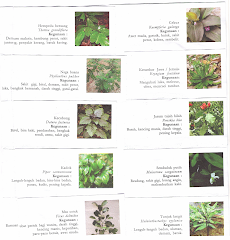

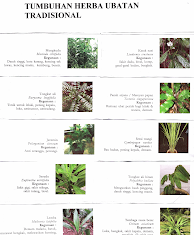

Tongkat Ali

Tongkat Ali

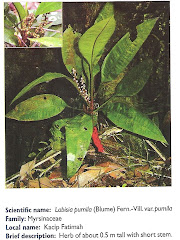

herba kacip Fatimah

herba Kacip Fatimah

hempedu beruang

hempedu beruang

hempedu bumi

hempedu bumi

herba misai kucing

herba misai kucing

herba tongkat Ali

.png)

Tongkat Ali

Ulama'

Ulama'

kapal terbang milik kerajaan negara ini yang dipakai pemimpin negara

kapal terbang

Adakah Insan ini Syahid

Syahid

Tok Ayah Haji Ismail

Saifuddin bersama Zakaria

Dinner....

Sukacita Kedatangan Tetamu

Pengikut

Kalimah Yang Baik

Ubi Jaga

Ubi Jaga

Arkib Blog

Burung Lang Rajawali

Chinese Sparrowhawk

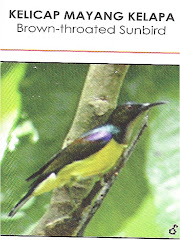

Kelicap Mayang Kelapa

Brown-Throated Sunbird

Kopiah

Pokok Damar Minyak

Kacip Fatimah

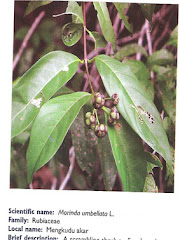

Mengkudu Akar