UNIVERSITI ISLAM ANTARABANGSA MALAYSIA

ATTITUDE MEASUREMENT AND CHANGE

DR HARIYATI SHAHRIMA ABDUL MAJID

NAZRIN

MOHD SAIFUDDIN MAT YUNUS

ZULHIJJAH 1430 HIJRIYAH

Performance appraisal rating, supervisor-subordinate relationship and their implication on employee job satisfaction attitude.

Performance appraisals are used widely in many organizations for administrative decisions, such as for promotions, pay raises, and termination of contracts, and also for developmental purposes. Whatever the use of the performance appraisal, the effectiveness of the appraisal system boils down with employee satisfaction of the system particularly during the performance feedback session in which employee were informed of their achievement by their immediate supervisor.

Keeping and Levy (2000) conceptualised appraisal satisfaction in three ways: (a) satisfaction with the appraisal interview or session, (b) satisfaction with the appraisal system, and (c) satisfaction with performance ratings. Probably the single most important information that employees have about the performance appraisal system is the actual ratings they receive, because these signify recognition, status, and future prospects within the organization. Moreover, when ratings fall short of ratees’ expectations; unfavorable attitudes often develop (Lam, Yik, & Schaubroeck, 2002). Performance appraisal feedback involved interaction between supervisor and their subordinate and from the study by Whiting, Kline and Sulsky (2007), satisfaction with performance appraisal is dependent on supervisor-subordinate relationship in which trust and supportiveness of a supervisor predict the level of employee satisfaction.

In this paper we investigated the effect of performance rating, affective state and supervisor subordinate relationships on employee’s job satisfaction attitude. Particularly we were interested to know;

How these variables are related to each other?

And what types of relationships that exist between them?

The study adopted the Affective Event Theory (AET) model developed by Weiss and Cropanzano with level of performance rating, individual affective state and supervisor-subordinate relationship as input variables and job satisfaction attitudes at the outcome.

Work attitudes and the consequences of appraisal feedback satisfaction.

Attitude according to the definition is a learned predisposition to respond positively or negatively to a specific object, situation, institution or a person and comprises of three components namely affective, behavioral and cognitive (Hariyati Sharima A Majid, 2009). “In the context of work psychology, many job-related attitudes have been studied by psychologist, but the two most commonly studied are job satisfaction and organizational commitment” (Aamodt, 2007, p. 335). The attribution of organizational commitment as an attitude has been widely acknowledge by many researches such that Meyer (as cited in Doyle, 2003) summarised organizational commitment comprises of three distinct components; desire to maintain membership (affect), belief in and acceptance of the values and goals of an organization (cognition), and willingness to exert effort on behalf of the organization (behavior). On the other hand, job satisfaction has always been conceptually defined only as an affect (Brief, 1998). Building from the working definition of Locke in which job satisfaction is a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences, Brief defined job satisfaction as an internal state that is expressed by affectively and/or cognitively evaluating an experienced job with some degree of favor or disfavor. This definition in the essence captures the affective and cognitive components of an attitude but not the behavioral component, to this Brief explained that the exclusion of behavior responses was because they often are considered consequences of job satisfaction. In another perspective in defining job satisfaction as an attitude, Weiss (2002) asserted that the fundamental property on an attitude is the evaluation process. In operationalising attitude, basic attitude measures ask respondents to place the attitude object along a scale of evaluation and in the case of job satisfaction, although normally measurement is phrased in ways that make them seem like they are tapping affective states but make no mistake, evaluation is the essential construct being measured.

There are many factors that have been describe as the antecedents of organizational commitment and job satisfaction, Brief (1998) for example in his discussion on antecedents for job satisfaction argued that personalities and objective circumstances of one’s jobs influence their job satisfaction level. Brief added that the objective circumstances of job are the facets of the job that exist external to the mind of the job occupant whose job satisfaction is of interest. These facets might include for example pay level, hours worked and status attached to the job. Organizational commitment on the other hand also shares similar antecedents as job satisfaction. Van Dyne and Graham (as cited in Coetzee, 2005) described that various personal, situational and positional factors can affect one’s organizational commitment.

Bearing on the discussion by Brief (1998) and Van Dyne (as cited in Coetzee, 2005) we focus our study on appraisal feedback satisfaction as job facet or situational factor that will have an implication towards one work attitude outcomes. The study of appraisal feedback satisfaction and work attitudes has long been investigated by many researches. Satisfaction with appraisal feedback however can be attributed through many feedback related factors, according to Jawahar (2006b) they are four significant factors which have been commonly established by many researchers independently, these are satisfaction with performance appraisal rating, satisfaction with appraiser, satisfaction with appraisal system and participation during the performance appraisal feedback session. Using the hierarchical regression to test these four factors in one study, Jawahar established that there are a significant relationship between employees’ appraisal satisfaction with performance rating (ΔR2 = .167, β = .43, t = 3.583, ρ< .001), satisfaction with rater (ΔR2 = .144, F = 14.212, β = .42, t = 3.77, ρ< .001) and performance appraisal system (ΔR2 = .07, F = 5.962, β= .27, t = 2.45, ρ< .05), whilst employee participation during performance feedback session was only partially supported. Testing for unique variance of each predictor on appraisal satisfaction, Jawahar established that only satisfaction with rater (sR2 = .16, β = .473, t = 4.028, ρ< .001) and performance rating (sR2 = .06, β = .29, t = 2.472, ρ< .05) explained unique variance in satisfaction with appraisal feedback. The study of Jawahar had also indicated that gender, age, tenure and department do not explain any variance in satisfaction with appraisal feedback.

Focusing on the effect of performance rating on work attitude, a longitudinal study by Pearce and Porter (1986) on the effect of performance rating on organizational commitment, indicated that those who received relatively low performance rating register a significant dropped in organization commitment and remain significantly low a year later while the commitment of those who received high rating remain stable over the study period. Extending Pearce and Porter finding with the inclusion of individual dispositional factor over a study period of six months, Lam, Yik, and Schaubroeck, (2002) found that the immediate reaction of employees either with high or low negative affectivity trait revealed a similar results in which upon receiving a positive appraisal rating, the employee’s organizational commitment and job satisfaction at time 2 were significantly higher than their respective level at time 1 despite the return to normal on work attitudes for those with high negative affectivity at time 3 whilst the work attitudes of those with low negative affectivity trait remain relatively stable. However contrary to the significant finding of Perce and Porter on negative performance rating and organizational commitment, Lam et al., result do not revealed a significant relationship between negative performance rating, job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

In a cross sectional study by Jawahar (2006a) on the consequences of feedback satisfaction toward organizational commitment and job satisfaction, conducted on 256 employees from a software development company in the US West Coast, results also indicated that satisfaction with appraisal feedback significantly correlate with employee job satisfaction (r = .32, p <.001) and organizational commitment (r = .18, p <.01) four weeks after the company conducted their performance evaluation exercise. In this study Jawahar had also established the usefulness of feedback satisfaction with work attitudes such that satisfaction with appraisal feedback explain and additional 5% variance in organizational commitment (ΔR2 = .05, F = 12.34, p <.001) and an additional 38% of the variance in job satisfaction (ΔR2 = .38, F = 156.28, p<.001) thus providing evidence of discriminant validity on the important of appraisal feedback satisfaction.

Appraisal feedback, affective state and work attitude

While satisfaction with appraisal feedback was shown to be linked with subsequent employees’ work attitudes; there is also an indication that one’s affective state plays an intermediary role in shaping his/her work attitudes. Jawahar (2006a), while building up the hypothesis on appraisal feedback satisfaction and the corresponding job satisfaction, Jawahar cited that satisfaction with appraisal feedback is likely to enhance employees' feelings of self-worth and their feelings of positive standing within the organization. Consequently, employees' overall attitude toward their work and job situation should improve resulting in higher levels of job satisfaction. This statement correspond to affectivity (or emotion) of a person as a result of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the performance appraisal feedback that subsequently shape his/her work attitudes. According to Judge, Scott and Ilies (2006) through the affective event theory (AET), work environment in general and work events in particular lead to affective reactions (e.g., anger, joy) experienced at work, which then lead to work attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction). According to Ilies, De Pater, & Judge, (2007) appraisal feedback can be considered as an affective event that influences individuals’ behaviors through its influences on their emotions. These assertions of Judge et al. and Ilies et al. are substantiated in the following research empirical results.

Keeping and Levy (2000) defined affectivity to have positive and negative dimensions. Positive affectivity can be described through 6 adjectives namely happy, optimistic, good, confident, proud, and pleased with myself while negative affectivity as agitated, angry, annoyed, bothered, disgusted, and irritated. In the research conducted on over 208 respondents in a large international organization, it was found that satisfaction with appraisal feedback correlate significantly with positive affect (r = .29, p <.01) and negative affect (r = - .27, p <.01). Ilies et al., (2007), finding also supported that of Keeping and Levy, using regression analysis the pooled slope for predicting positive affect with feedback was positive and significant (λ10 = .07, p <.01) and the pooled slope for predicting negative affect was negative and also significant (λ10 = - .04, p <.01) allowing Ilies et al., to conclude that a positive feedback increases the positive affect and at the same time decreases the negative affect. While the above two studies linked appraisal feedback to affective state, we have not managed to obtain a specific empirical paper that provide a complete linkage between appraisal feedback, affective state and work attitudes. However in the study conducted by Mignonac and Herrbach (2004) pooling together a number of affective events that include receiving negative performance evaluation; their findings indicated that the negative affective states is significantly linked with job satisfaction and organizational commitment attitudes.

The premise of AET is that affect mediates the effect of organizational variables on attitudinal and behaviour outcomes (as cited in Mignonac and Herrbach, 2004). Testing for this mediating role, a partial support to AET assertion was found such that only the effect of negative events on job satisfaction and affective commitment was no longer significant when the affective state was controlled.

Supervisor-subordinate relationship

Reference to earlier discussion on satisfaction with appraisal feedback, Jawahar (2006b) had indicated that satisfaction with supervisor as one of the main factor influencing employee feedback satisfaction with higher statistical result as compared to performance rating. In fact in a review by Fletcher (n.d.) on factors determining the effect of feedback, he quoted “Whatever happens in an appraisal has to be seen against the background of the existing relationship between the manager and the subordinate. One sometimes hears the opinion expressed on appraisal training courses that ‘if we had good managers, we would not need appraisal’”.

One of the popular theories describing the supervisor-subordinate relationship is the Leader Member Exchange Theory or simply knows as LMX. Burton, Sablynski and Sekiguchi (2008) cited that the theory of LMX appeared about 30 years ago described as a dyadic relationships and work roles are developed and negotiated over time through a series of exchanges between leader and member. Bhal, Gulati and Ansari (2008) cited that different subordinates will have a different kind of work relationship with his/her supervisor and that high LMX members enjoy high exchange quality relationships as characterized by liking, loyalty, professional respect, and contributory behaviors. This quality of work relationship between the supervisor and subordinate in turn influence a variety of individual and organizational outcomes such as organizational commitment, job satisfaction, goal commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, career satisfaction and salary progression and turnover (as cited in Burton et al., 2008).

Studies of work event or work situation that include supervisor-subordinate relationship in the equation mainly revealed a mediating or a moderating role of LMX in determining the effect on work outcomes. Burton et al. (2008) study for example, revealed the mediating role of LMX on interactional justice and the outcome on job performance and organizational citizenship behavior and the moderating role of LMX on procedural and distributive justice and the outcome on organizational citizenship behavior. It is interesting to note that justice in general which refers to an individual’s perception or evaluation of the appropriateness of some process or outcome (as cited in Burton et al., 2008) are affected in a different manner by LMX. Burton et al. explained that interactional justice which is within one’s spherical of control, involved social exchange between the supervisor and subordinate and therefore LMX play a mediating role in determining subordinate work outcomes. Procedural and distributive justice on the other hand are more structural in nature involving the relationship between employees and their organization and therefore LMX play the moderating role in determining work outcomes. In the context of satisfaction with appraisal rating, affective state and the implication on work outcomes such as one’s job satisfaction and organizational commitment outcomes, therefore it can be argued that supervisor-subordinate relationship shall have a mediating role in governing the relationships as the appraisal feedback is within the direct control of one’s supervisor.

This study

In the context of our study we will only be focusing on job satisfaction attitude and its relationship with appraisal rating satisfaction, affective state and supervisor-subordinate relationship in the interest of simplicity as well as to control the number of variables therefore the number of questionnaires that our respondent will be subjected into. It is worth to note that, if organizational commitment is to be included, three distinct dimensions of commitment namely the affective, normative and continuance commitments need to be tested therefore increasing the number of variables.

The study adopted a cross sectional approach in the interest of timing as it has been shown to produce result based on the findings of Jawahar (2006b). However in term of timing between the last appraisal feedback and this study, the period of lapses was between 4-6 months as compared to Jawahar, which is 4 weeks after the respondents’ last performance appraisal feedback. The Affective Event Theory (AET) was adopted as the framework in linking our variables of interest. In the AET framework developed by Weiss and Cropanzano (as cited in Mignonac and Herrbach, 2004), the work environment features influence positive or negative affective events that shape individual affective state that may in turn lead to proximal affect-driven behaviours and contribute to the formation of work attitudes, the later also being influenced by a stable work environment features. Finally work attitudes influence judgement-driven behavior. Figure 1 illustrated the complete AET framework.

Figure 1: Affective Event Theory Framework

In the context of our study, based on the literature as presented in the earlier section of this paper, we modified the AET framework as depicted in Figure 2 therefore answering our first research question on ‘how these variables are related to each other’. Through the studies that have been conducted, satisfaction with appraisal feedback is related to employee job satisfaction attitudes, however the introduction of affective states and supervisor-subordinate relationship variables have been shown or partly shown to play a mediating role in explaining the relationship between satisfaction with appraisal feedback and job satisfaction attitude. Therefore in our model we captured the supervisor-subordinate relationship and affective state as an intermediary between satisfaction with appraisal feedback and job satisfaction attitude therefore potentially answering our second research question on ‘what types of relationships that exist between them’.

Figure 2: Satisfaction with appraisal rating, affective state, supervisor-subordinate relationship and job satisfaction

From this relationship we hypothesises that;

H1: Level of satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback through received performance rating is linked with individual job satisfaction attitude.

H2a: Level of satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback through received performance rating is linked with individual affective state (PA, NA) and with the quality of supervisor-subordinate relationship.

H2b: Satisfaction with appraisal rating increases positive affectivity while decreasing negative affectivity and dissatisfaction with appraisal rating create the opposite on one affective state.

H3: Affective (PA, NA) state and Supervisor-subordinate relationship mediate the relationship between satisfaction with appraisal feedback and job satisfaction attitude

2. Method

Participants

Participants for the study were selected from two organizations involving 65 potential respondents from two organisations in the Klang Valley, Kuala Lumpur and Kuantan, Pahang.

Measurement

Four measurement instruments were adopted in this study, all of the instruments include an option for a neutral kind of response and therefore for this study, all scales have been reduced by one option to avoid unnecessary undecided response from the participants.

Satisfaction with performance appraisal rating

The scale was a combination of three (3) Dulebohn and Ferris (1999) Procedural Justice in Performance Appraisal and Sweeney and two (2) McFarlin (1997) Distributive and Procedural Justice instruments measuring items that relate to satisfaction with appraisal rating. For the purpose of this study the respond scale consists of 4-point Likert scale of 1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree. Total scores larger than 10 shall indicate employee satisfaction with the performance appraisal rating. Examples of items from this scale are “The supervisor rated you on how well you did your job, not on his/her personal opinion of you” and “My performance rating presents a fair and accurate picture of my actual job performance”

Job Satisfaction

The scale was adopted from Brayfield and Rothe (1951) 18-items Overall Job Satisfaction. For the purpose of this study the respond scale consists of 4-point Likert scale of 1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree. Item 3, 4, 6, 8, 11, 14, 16 and 18 are reverse score items and therefore shall be recoded before statistical analysis. Total scores of larger than 36 shall indicate employee does have job satisfaction. Coefficient alpha ranges from .88 to .91. Examples of items from this scale are “My job is like a hobby to me”, “I am often bored with my job” and “Most days I am enthusiastic about my work”.

Job Affect

The scale was adopted from the 20-items Job Scale Affect as cited in Brief (1998) of 10 positive affect items and 10 negative affect items. The scale consists of 7-point Likert scale of 1 = Extremely Slightly to 7 = Extremely Strongly. For the purpose of this study, 4-items of the scale have been dropped off from the questionnaire after discussion with research supervisor as it was not deem appropriate in our study context. The dropped items are “Peppy”, “At rest”, “Elated” and “Placid” however as the scale has an equal number positive and negative affective items another three negative and one positive item was also dropped to balance off the scale. Items 3, 4, 7, 8, 10 and 11 are the negative affect items which will be recoded for the purpose of statistical analysis. Total scores of larger than 48 shall indicate employee positive affectivity towards performance appraisal feedback

Supervisor-subordinate relationship

The scale was adopted from Scarpello and Vandenberg (1987) 18 items Satisfaction with supervisor. For the purpose of this study the respond scale consists of 4-point Likert scale of 1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree. Total scores of larger than 36 shall indicate subordinate satisfaction with his/her supervisor. Coefficient alpha ranges from .95 to .96. Examples of items from this scale are “The way my supervisor is consistent in his/her behaviour toward subordinates”, “The way my supervisor informs me about work changes ahead of time” and “The way my supervisor shows concern for my career progress”.

Procedures

Questionnaire used both English and Malay as a medium of communication as respondents are coming from various educational backgrounds. Translation of the four scales from English to Malay was conducted through internet translator and is cross check with a medical doctor and the research supervisor to determine appropriateness of the translation.

Respondents were presented with a booklet of questionnaire that contains the scales for the four variables. In the case of appraisal feedback satisfaction and affective states, instructions were given for them to answer by remembering the event that had occurred during the last appraisal feedback session. In the case of supervisor-subordinate relationship they have to answer by referring to the most recent supervisor with at least six months of working experience and finally for job satisfaction, the instruction was for them reflect their current experience at work.

Statistical procedures used to analyse the survey feedback are;

Descriptive statistic and one sample t-test to determine scores for variables and its significant against the test value,

correlation analysis to determine the general relationship between variables,

paired sample t-test to verify the significant differences between the increasing positive and decreasing negative affectivity or vice versa and

regression analysis to determine the mediating role of affective state and supervisor-subordinate relationship; 1) appraisal feedback satisfaction must affect the mediators, 2) the mediators must affect job satisfaction attitude, 3) appraisal feedback satisfaction must affect job satisfaction and 4) the effect of appraisal feedback satisfaction on job satisfaction reduces to zero when the mediators are control (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

3. Results

Demographics

A total of 54 participants return the questionnaire of which 2 have to be discarded as they did not provided the answer to two (2) or more items in the questionnaire. 28 (53.8%) of the participants are female, 23 (44.2%) are male and 1 (1.9%) did not classify his/her gender. 24 (46.2%) of the participants are with a degree qualification, 11 (21.2%) with SPM, 13 (25.0%) with STPM/Diploma and 3 (5.8%) with a Master Degree while the remaining 2 did not classify their qualification.

Descriptive Statistic

The mean score for performance rating was 14.77 (SD = 2.88). The value of t (51) = 12.00 (ρ = 0.01) indicate a significant different between participants performance rating total score against the test value of above 10.00 which signify respondents satisfaction with performance appraisal rating. The mean score for job satisfaction was 51.06 (SD = 7.33). The value of t (51) = 14.82 (ρ = 0.01) indicate a significant different between participants job satisfaction total score against the test value of above 36.00 which signify respondents job satisfaction. The mean score for affective state was 59.08 (SD = 10.73). The value of t (51) = 7.48 (ρ = 0.01) indicate a significant different between participants affective state total score against the test value of above 48.00 which signify positive affectivity. The mean score for supervisor-subordinate relationship was 48.00 (SD = 10.06). The value of t (51) = 8.60 (ρ = 0.01) indicate a significant different between participants total score against the test value of above 36.00 which signify respondents satisfaction with his/her supervisor. Table 1 describes the descriptive result for the four variables.

Table 1: Descriptive statistic for the four variables (n=52)

Variable Mean Std Deviation Test Value t Ρ

Performance Rating

14.77 2.88 >10 12.00 .01

Job Satisfaction

51.06 7.33 >36 14.82 .01

Affective State

59.08 10.73 48 7.48 .01

Supervisor-Subordinate

48.00 10.06 >36 8.60 .01

Correlation

Correlational analyses between the four variables are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2: Correlation between the variables (n=52)

Variable 1 2 3 4

Performance rating

-

Job satisfaction

.03 -

Affective state

.36** .33** -

Supervisor-Subordinate

.60** -.01 .30* -

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Paired sample t-test

Paired sample t-test between the positive and negative affectivity is illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3: Paired sample t-test for positive-negative affectivity (n=52)

Item Mean Std. Deviation t Ρ

Positive-negative affectivity

11.83 10.71 7.66 .01

Regression

Regression analysis to test for mediation is illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4: Regression analysis to determine mediator effect on Job Satisfaction (n=52)

Independent Variable Affect Supervisor-subordinate Job satisfaction

Performance rating

.36** .59** .03

Affect state

- - .33*

Supervisor-subordinate

- - -.01

** Significant at the 0.01 level

* Significant at the 0.05 level

Coefficients are standardized betas

Hypotheses testing

H1: Level of satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback through received performance rating is linked with individual job satisfaction attitude.

Correlational analysis between satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback and job satisfaction yielded insignificant relationship between these two variables, therefore hypothesis 1 is not supported by this study

H2a: Level of satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback through received performance rating is linked with individual affective state (PA, NA) and with the quality of supervisor-subordinate relationship.

Correlational analysis between satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback and individual affect yielded significant relationship between these two variables (r = .36, ρ = .01). Correlational analysis between satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback and satisfaction with supervisor-subordinate relationship yielded significant relationship between these two variables (r = .60, ρ = .01). Therefore hypothesis 2a is supported by this study

H2b: Satisfaction with appraisal rating increases positive affectivity while decreasing negative affectivity and dissatisfaction with appraisal rating create the opposite on one affective state.

Paired sample t-test between positive and negative affectivity yielded significant differences between these two variables t (47) = 7.66 (ρ =.01), therefore hypothesis 2b is supported by this study

H3: Affective (PA, NA) state and Supervisor-subordinate relationship mediate the relationship between satisfaction with appraisal feedback and job satisfaction attitude

Regression analysis was able to predict a significant relationship between appraisal feedback satisfaction with the two mediators, however only one mediator, the affective state predicts a significant relationship with job satisfaction and finally the appraisal feedback satisfaction itself does not predict a significant relation with the job satisfaction attitude. Reference to the steps listed by Baron and Kenny (1986) to test for mediation, the finding from this study does not support the mediator role of supervisor-subordinate relationship and affective state as suggested by other researchers in explaining the relationship between appraisal feedback satisfaction and job satisfaction. Therefore Hypothesis 3 is not supported by this study.

4. Discussions

In this paper we have established the relationship between the appraisal feedback satisfactions, affective state, supervisor-subordinate relationship and job satisfaction as illustrated in Figure 2 in the ‘This study’ section therefore answering our first research question on ‘How these variables are related to each other?’. In general the respondents indicated that they are experiencing satisfaction with their appraisal feedback through performance rating received, positive affective state, satisfaction in their supervisor-subordinate relationship and job satisfaction. Most of these variables are significantly correlated between each other through correlation analysis except for the relationship between performance rating with job satisfaction and supervisor-subordinate relationship with job satisfaction.

Despite indication from other researchers that performance rating and supervisor-subordinate relationship are correlated with job satisfaction, our findings have not managed to obtain a similar results. These discrepancies could be attributed, first to our survey method such that it was conducted at a longer time lapses after the respondents’ last experience with appraisal feedback. We suggest that with this longer time period and that satisfaction with appraisal feedback correlation with job satisfaction is relatively not that strong, r = .32 (Jawahar, 2006a), other factors could have play an important roles that contribute towards one’s job satisfaction. Secondly since our numbers of respondents are quite small as compared to the number of items posted in the questionnaire, it might also have an impact to our study results. On the satisfaction with supervisor-subordinate relationship, the quality of relationship according to LMX should influence one’s job satisfaction (as cited in Burton et al., 2008). The discrepancies in our result could be attributed to one’s internal affectivity playing a more important role in determining job satisfaction as compared to the relationship with their supervisor. While supervisor-subordinate relationship plays an important role in determining satisfaction with appraisal feedback compared to affectivity, job satisfaction on the other hand is affected by other factors encounter in the job than the relationship alone similar to the effect of performance rating on job satisfaction. This is on line with Brief (1998) suggestions that facets associated with the job play an important role in determining the job satisfaction. However in the case of affectivity, it is something internal to a person that finally contributes in shaping one’s job satisfaction. Furthermore we also acknowledge the size of our respondents’ impact on the final result of our study. Since these two relationships (i.e. appraisal feedback satisfaction – job satisfaction and supervisor-subordinate relationship – job satisfaction) are not in line with the hypotheses, therefore the mediating role of supervisor-subordinate relationship and affective state could not be tested since the four steps as listed by Baron and Kenny (1986) have not been fulfilled.

Returning to our second research question on ‘What types of relationships that exist between them?’ in theory we have established the relationship however as our results have indicated otherwise as described in the previous paragraph, we have not managed to empirically answer this second question.

This paper is mainly limited in its methods, in the number of respondents in relation to items in our questionnaire and the timing, as the study was conducted after a lapse of about 4-6 months. Therefore in future research these considerations should be undertaken as in a cross sectional study, a lot of factors such as respondent state of mind, room temperature and understanding to instruction are not under the control of the researcher. A bigger number of respondents on the other hand would mean a better representation of a population and therefore could contribute to the final result accuracy. Appraisal feedback satisfaction is just one of the many facets one’ encounter in his/her job and a longer lapses of time between the actual appraisal feedback session and the study would mean many other factors would have taken its place in shaping individual job satisfaction.

References.

Aamodt, M. G. (2007). Industrial/organizational psychology: an applied approach (5th ed.). United States of America: Thomson & Wadsworth

Baron, R. M. and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychology: conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182

Bhal, K. T., Gulati, N., and Ansari, M. A., (2008). Leader member exchange and subordinate outcomes: test of mediation model. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal, 30(2), 106-125

Brief, A. P. (1998). Attitudes in and around organization. London: Sage Publications

Burton, J. P., Sablynski, C. J., and Sekiguchi, T., (2008). Linking justice, performance, and citizenship via Leader–Member Exchange. Journal Business Psychology, 23, 51-61

Fletcher (n.d.). The effect of performance review in appraisal: evidence and implications. Journal of Management Development, 5(3), 3-12.

Ilies, R., De Pater, I. E., and Judge, T. (2007). Differential affective reactions to negative and positive feedback, and the role of self-esteem. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 22(6), 590-609.

Jawahar, I. M. (2006a). An investigation of potential consequences of satisfaction with appraisal feedback. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 13(2), 14-28.

Jawahar, I. M. (2006b). Correlates of satisfaction with performance appraisal feedback. Journal of Labour Research, XXVII (2), 213-236.

Judge, T. A., Scott, B. A., and Ilies, R. (2006). Hostility, job attitudes, and workplace deviance: test of a multilevel model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 126–138.

Keeping, L. M. and Levy, P. E. (2000). Performance appraisal reactions: measurement, modeling, and method bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 708-723.

Lam S. S. K., Yik M. S. M., and Schaubroeck J., (2002). Responses to formal performance appraisal feedback: the role of negative affectivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 192–201

Mignonac and Herrbach, (2004). Linking work events, affective states and attitudes: an empirical study of managers’ emotions. Journal of Business Psychology, 19(2), 221-240.

Pearce, J. L. and Porter L. W. (1986). Employee responses to formal performance appraisal feedback. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 211-218.

Weiss, H. M. (2002). Deconstructing job satisfaction Separating evaluations, beliefs and affective experiences. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 173-194.

Whiting, H. J., Kline T. J. B., Sulsky L. M., (2007). The performance appraisal congruency scale: an assessment of person-environment fit. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 57(3), 223-236.

أَلَمْ تَرَ أَنَّ اللَّهَ يُسَبِّحُ لَهُ مَنْ فِي السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالأرْضِ وَالطَّيْرُ صَافَّاتٍ كُلٌّ قَدْ عَلِمَ صَلاتَهُ وَتَسْبِيحَهُ وَاللَّهُ عَلِيمٌ بِمَا يَفْعَلُونَ Tidakkah kamu tahu bahwasanya Allah: kepada-Nya bertasbih apa yang di langit dan di bumi dan (juga) burung dengan mengembangkan sayapnya. Masing-masing telah mengetahui (cara) solat dan tasbihnya, dan Allah Amat Mengetahui apa yang mereka kerjakan. an-Nur:41

Tazkirah

Sami Yusuf_try not to cry

mu'allim Muhammad Rasulullah Sallallahu alaihi waSalam

ummi_mak_mother_ibu_Sami Yusuf

zikir Tok Guru Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat Mu'allimul Mursyidi

syeikh masyari afasi

ruang rindu

song

Arisu Rozah

Usia 40

Mudah mudahan diluaskan rezeki anugerah Allah

usia 40 tahun

UPM

Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

pemakaian serban semsa menunaikan solat_InsyaAllah ada sawaaban anugerah Allah

Rempuh halangan

Abah_menyokong kuat oengajian Ijazah UPM

usia 39 tahun

usia 23 tahun_UPM

An_Namiru

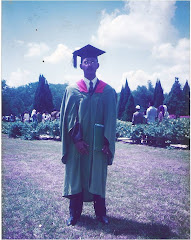

Ijazah Pengurusan Hutan UPM

General Lumber_Nik Mahmud Nik Hasan

Chengal

Tauliah

Semasa tugas dgn general lumber

PALAPES UPM

UPM

Rumah yang lawa

Muhammad_Abdullah CD

semasa bermukim di Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

Ijazah

air terjun

Borneo land

GREEN PEACE

GREEN PEACE

Kelang

Ahlul Bayti_ Sayid Alawi Al Maliki

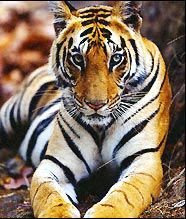

Asadu_ Tenang serta Berani

atTiflatul Falasthiniin

Sayid Muhammad Ahlul Bayt keturunan Rasulullah

AnNamiru_SAFARI_Kembara

AnNamiru_resting

Hamas

sabaha anNamiru fil nahri

Namir sedang membersih

Tok Guru Mualimul_Mursyid

An_Namiru

.jpg)

Namir_istirehat

.jpg)

SaaRa AnNamiru fil_Midan

.jpg)

Renungan Sang Harimau_Sabaha AnNamiru

.jpg)

Syaraba AnNamiru Ma_A

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNimru ma_A waladuha

Namir fil_Ghabi (sebut Robi...

Namir

AdDubbu_Beruang di hutan

Amu Syahidan Wa La Tuba lil_A'duwwi

AsSyahid

Namir

Tangkas

najwa dan irah

sungai

najwa

najwa

Kaabatul musyarrafah

unta

Jabal Rahmah

masjid nabawi

masjid quba

dr.eg

najwa dan hadhirah

along[macho]

![along[macho]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjuMi7D33CmR0_KXrCW2XigfLcUuQurcvtqOS139ncCwEzCyB-jUopk7QK7anADIenJEm2S0N6gAY1ubnACYXewgiAsI3rBjnLTawM39alLL-rEopOoVqn0w5WpLhPJH3hrXNtchEhgtyaI/s240/P7150023.JPG)

harissa dan hadhirah

adik beradik

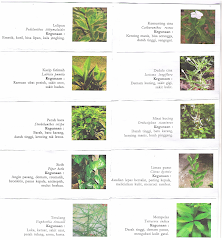

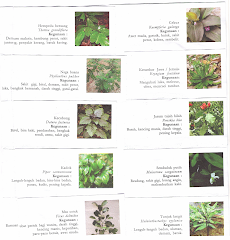

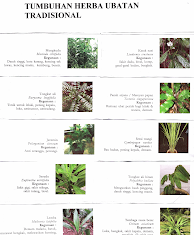

Tongkat Ali

Tongkat Ali

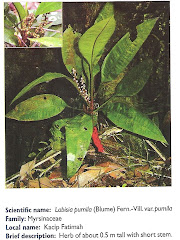

herba kacip Fatimah

herba Kacip Fatimah

hempedu beruang

hempedu beruang

hempedu bumi

hempedu bumi

herba misai kucing

herba misai kucing

herba tongkat Ali

.png)

Tongkat Ali

Ulama'

Ulama'

kapal terbang milik kerajaan negara ini yang dipakai pemimpin negara

kapal terbang

Adakah Insan ini Syahid

Syahid

Tok Ayah Haji Ismail

Saifuddin bersama Zakaria

Dinner....

Sukacita Kedatangan Tetamu

Pengikut

Kalimah Yang Baik

Ubi Jaga

Ubi Jaga

Arkib Blog

Burung Lang Rajawali

Chinese Sparrowhawk

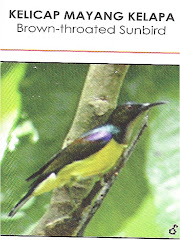

Kelicap Mayang Kelapa

Brown-Throated Sunbird

Kopiah

Pokok Damar Minyak

Kacip Fatimah

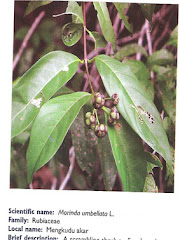

Mengkudu Akar