Abstract:

The leadership theories presented in this research are representative of four different eras. The Trait era which began in the early 19th century correspond to the early period as delineated by Wren (2005), the theory of Bureaucracy advanced by Max Weber (1864-1920) and representative of the scientific management era, the theory of Mary Parker Follett (1886-1933), which arises out of what Wren (2005) referred to as “the social person era” and the theory of Renesis Likert (1903-1981) which underscores the modern era. These four perspectives provide the basis for a comprehensive review of leadership theories within the context of their similarities and differences and a concluding discussion on how they might address contemporary leadership issues and challenges. This paper is not an attempt to discuss the four theories from a historical perspective; rather it purposes to give some thoughts for reflection on how theories of leadership influence practices in today’s organizations.

Working Paper Series Mark Esposito

Dexter Philips

The Similarities and Differences between four

Leadership Models and How They Might

Address Contemporary Leadership Issues and

Challenges

Supervised by: Dr. Mark Esposito

Abstract

The leadership theories presented in this research are representative of four

different eras. The Trait era which began in the early 19th century correspond to

the early period as delineated by Wren (2005), the theory of Bureaucracy

advanced by Max Weber (1864-1920) and representative of the scientific

management era, the theory of Mary Parker Follett (1886-1933), which arises out

of what Wren (2005) referred to as “the social person era” and the theory of

Renesis Likert (1903-1981) which underscores the modern era. These four

perspectives provide the basis for a comprehensive review of leadership theories

within the context of their similarities and differences and a concluding

discussion on how they might address contemporary leadership issues and

challenges.

This paper is not an attempt to discuss the four theories from a historical

perspective; rather it purposes to give some thoughts for reflection on how

theories of leadership influence practices in today’s organizations.

About the authors

Dexter R. Phillips is a native of Georgetown, Guyana South

America/Caribbean. He has been involved the education for the last 17 years, 10

of which relates to his International Teaching Career in International Colleges

and Schools in the Caribbean, United Kingdom, Philippines and currently

Suzhou Singapore International School China.

At the functional level Dexter’s career spans across a number of administrative

and teaching positions, some of which include, Vice Principal, Dean of students’

affairs, College Careers Counselor, International Baccalaureate Diploma

Coordinator, Head of Humanities and teacher of Business Management and

Economics. He is also an examiner and Internal Assessment Moderator for

Business and Management with the International Baccalaureate Organization

(IBO), Associate Professor of Business Studies at Nations University - School of

the Nations in Georgetown Guyana and has recently published a Business and

Management text book – Higher and Standard Levels Business and Management

Revision Notes for use with the International Baccalaureate Diploma

Programme.

Academically, Dexter holds an International Graduate Teaching Diploma from

the University of Cambridge, a Master of Business Administration from the

University of San Carlos, Cebu Philippines and an Educational Doctorate (Ed.D)

– Major in Institutional Planning from the University of Cebu.

Dexter is currently a doctoral candidate of Business Administration at the Swiss

Management Centre –University (SMC-U).

Mark Esposito, Ph.D. (who has supervised the paper) is an Associate

Professor of Management and Behavior at Grenoble Ecole de Management and a

Research Fellow at the Swiss Management Center.

Introduction

As long as there have been human endeavors, people have always been willing to

take charge of planning, organizing and controlling work (Friesen, and Johnson

1995). One might say that nature abhors a vacuum and someone will always step

forward to fill a leadership void, hence, a natural emergence of leadership. Miller

(1989) subscribes to Johnson’s thoughts by arguing that such natural emergence grew

out of the human instinct for survival in an era where, meeting food, shelter, and

safety needs of communities required cooperative efforts and such efforts had to be

coordinated by some one with the capacity to direct human endeavors in productive

and other activities required for sustaining and building the community.

It is this basic principle which underscores the emergence of leadership and

establishes the concept as a phenomenon rooted in ancient economic, political and

social systems. As humans develop from simple ways of living into more advanced

nations, complex forms of leadership supported by academic models and theories

evolved.

Today these models and theories which underpin the philosophical ideals of the

subject have had far reaching implications in shaping a more complex understanding

of leadership as a discipline and have given many insights into questions such as,

what character traits define a leader and what constitute excellent leadership

practices?

All activities of organizations public or private, religious or the family are impacted

either directly or indirectly by the established principles associated with leadership.

Organizational goals and objectives are accomplished through someone taking the

lead and responsibility for influencing and directing people and activities and

irrespective of whether such leadership is prudent or otherwise it does have

significant implications and continues to be cornerstone of man’s development or

down fall.

The trait era

Borgatta, Bales, and Couch (2001), believed that the great man theory is probably the

oldest theoretical perspective to have received attention throughout the evolution of

leadership thinking. In an era when scholars were seeking some measure by which

leadership could be defined there was the widely acceptable belief that “leaders were

different from their followers and that since fate or providence was a major

determinant of the course of history, the contention that leaders were born, not made

was widely accepted by scholars and those attempting to influence the behaviour of

others” (Cawthon, 1996, p.3). Further developments on the nature of leadership

along this line of argument led to the advancement of trait theory of leadership as we

know it today.

The basic tenet of the trait theory is that leaders can be defined by certain

characteristics or traits and these are what separate them from the group or society to

which they belong (Navahandi, 2006). Consequently, the trait theory dictates that

leaders by virtue of their birth were endowed with special qualities that allow them

to lead others. The major assumption being, that “if certain traits or characteristics

can be used to distinguish between leaders and followers then existing political,

industrial, and religious leaders should possess them” (Navahandi,2006).

During the early period, proponents of the trait theory outlined five characteristics

which today are still considered the corner stones of all leadership theories: (1)

power, (2) intelligence, (3) persuasion, (4) personality and (5) charisma. As other

theories on how to lead and manage successful organizations became prominent,

scholars then found that although trait plays a role in determining leadership ability

and effectiveness, such role was minimal (Wren, 2005).

The new argument which gained much prominence in early and late 19th century

thinking on the subject was based on the notion that leadership should be viewed as

a group phenomenon which cannot be studied outside a given situation (Navahandi,

2006, p.38) and, thus, the bureaucratic theory which advocates the proper order of

doing things became the defining standard for leadership.

The bureaucratic versus the trait theory of leadership

While it cannot be said with certainty that there are considerable similarities between

the trait and Bureaucratic theories of leadership, a certain argument could hold true,

which is, if bureaucracy is defined by executive responsibilities that stress the

importance of the systemic development and application of rules (Clawson, 2002),

then there may be some justification for accepting the notion that some similarities

between these theories do exist. Further, since the trait theory is based on the notion

that power, intelligence, persuasion, personality and charisma are defining

parameters for leadership capabilities; the assumption is that similarities between the

theories do exist.

A careful consideration of the theory of bureaucracy proves the need to vest

authority and power in people. Wren (2005) contends that “some form of authority is

the cornerstone of any organization. Without it, no organization can be guided

towards an objective; authority brings order to chaos” (p.228). Such authority and

power, according to the bureaucratic theory of leadership, should be vested in people

“by virtue of their abilities and skills” (Clawson, 2000). Thus, from a bureaucratic

perspective, the notion is that power and responsibility is entrusted to the ‘common

man’ who exudes such qualities as outlined by the trait theory. Yet irrespective of the

similarities which can be found between the trait theory and some of the underlying

principles of bureaucracy, there exist a number of differences.

Beyond the concept of the ability to lead based on character traits, the bureaucratic

theory advances division of labour. Formal rules and regulations are considered as

the basis for enduring uniformity and discipline. The arranging of office positions in

a hierarchical order, the formal documentation of office authority with strict

adherence of its incumbent to such rules of authority, and the practice of hiring

managers from within differentiates the bureaucratic model of leadership from the

thought that traits are enough to ensure enduring leadership of organizations

(Clawson, 2000;Scott, 2005).

The theory of Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933) versus the trait and bureaucratic

theories

The thoughts of Mary Parker Follett (1868-1933) have significant implications for

leadership. According to Wren (2005), Follett’s theory spans five critical areas of the

leadership and management spheres; the group, conflict, business organization,

authority and power and task leadership.

With regard to the group, Follett believed that the essence of group principle is to

bring out individual differences and integrate them into unity” (Wren, 2005. p.303).

A close examination of this argument substantiates Follett’s conviction that people

are all not the same; they exude different characteristics, which is the basic tenet of

the trait theory. However, Follett did not stop with such mere recognition; she went

on to advocate that in the interest of unity of the whole group such characteristics

and individual interest must be set aside (Bartol and Martin, 1998).

Additionally, inherent in Follett’s theory is the recognition of a bureaucratic structure

of organization and society. The fact that she recognizes the existence of power and

authority gives credence to such assumption. For it cannot be argued, that by the

very nature of her theories on authority and power, such recognition of bureaucracy

is absent or nonexistent in her discourse. Wren (2005), best illustrate this line of

argument by stating that “in this second era, Follett sought to develop “power-with,

instead of power-over , and co-action to replace consent and coercion” (p.308). It

seems, therefore, that Follett’s theory of, “power-with instead of power-over” (Wren,

2005.p.308), sought to bring a new meaning to relationships which exists within

bureaucratic structures.

Another, similarity between Follett’s theory and the bureaucratic theory of

leadership can be cited from her reasoning that authority should be vested in people

with experience and the necessity to achieve goals through coordination and control

(Wren, 2005). She also cautioned that the most ingenious corporate structure means

nothing unless someone leads it well (Harrington, 1999). Similarly, bureaucracy

dictates the need for people in authority to occupy and office and the notion that

appointment to offices should be based on a personal expertise (Navahandi, 2006.

p.38).

In essence, the bureaucratic theory asserts the need for structured organizations with

strict defining rules and regulations while the trait theory is based on leadership of a

single individual or individuals exerting control over subordinates by virtue of

certain traits and characteristics. To bridge overarching principles underscoring these

theories Follett advocates integration.

On the other hand, the underpinning difference between the trait, bureaucratic and

Follett’s principles on leadership can be best explained by what she posit in her

discourse on the topic, what is absent from the trait and bureaucratic theories. Such

notions as, conflict should be resolved through integration of interests and obedience

to the law of the situation, power sharing, establishing good organization by creating

a feeling of working with rather than against someone, recognition that authority

resides not in the person or position but in the situation, and the “development of a

social consciousness, instead of individualism” (Wren, 2005; Scott, 2005; Bartol and

Martin, 1998) sets these three theories apart , yet offers much similarities.

Renesis Likert (1903-1981)

Renesis Likert (1903-1981), proposed a system of leadership and management which

focuses on the entire organization. His main argument was “of all the tasks of

management, leading the human endeavor are the central and most important one

because all else depended on how it is done” (Wren, 2005, p.442). Based on this

belief, Likert proposed a system of leadership which takes into consideration the

whole organization. His proposal pertains to aspects of the organization such as its

structure; methods, form and flow of communication, issues relating to motivation,

procedure for decision making, evaluation of employees and how members of the

organization relate to each other (Pugh and Hinings, 1981). The underlying premise

of Likert’s theory is that four systems of leadership pervade an organization and each

system is associated with certain leadership behaviour.

The first system is regarded as the exploitative authoritative system, the second

being the benevolent authoritative system, the third he describes as the consultative

system and the fourth as participative group’ system (Wren 2005).

The exploitative authoritative system is characterized by the use of coercion to

accomplish organizational goals; one way flow of communication from the top down

where decisions are imposed on subordinates, greater responsibilities for higher level

managers, limited scope for team work and a distant relationship between

supervisors and subordinates.

Under system benevolent, there are rewards for accomplishment of goals but

decision making is centralized. The system facilitates feedback of subordinates to

management, however, suggestions and recommendations are restricted to what

management considers as pertinent to the organization and their personal positions

as leaders. Also, while there is some amount of delegation at the lower levels,

leaders, expect their subordinates to be subservient.

In a consultative system, while major decisions are made at the top of the

organizational hierarchy there is a wider consultative approach which involves all

the internal stakeholders to be affected by the decision. Communication flows both

ways, that is, upwards and downwards but upward critical communication is

cautious (Pugh and Hinings, 1981).

The participative group system is defined by three basic concepts: “(1) the principle

of supportive relationship; (2) the use of group decision making and group methods

of supervision; and (3) setting high performance goals for the organization” (Wren,

2005, p.442).

Additionally, Wren (2005) found that Likert proposed a 5th system in which “an

organization’s hierarchy of authority would be replaced with a reciprocal system of

participation and influence and when there are conflicting situations, groups will

work together through overlapping memberships (‘link pins’) until a consensus

could be reached” (p.443). Such authority, Wren (2005) contends, “Would depend on

the interpersonal skills of creative leaders who had the ability to get others

committed and working towards organizational goals” (p.443).

Overall, the underlying principle of Likert’s theory is that leaders could adopt

behaviours to take account of the situation at hand (Pugh and Hinings, 1981).

The very nature of Likert’s outline of the “four types of leader behaviour” (Wren,

2005) attest to the similarity between his theory and the trait theory of leadership.

The similarity is found where leaders possess certain trait which causes them to

behave in a certain manner. Such behaviour determines a person’s style of leadership

and the extent to which that behavior is executed will have a positive or negative

effect on the organization’s performance as a whole. On the other hand, where there

are differences between Likert’s theory and the trait theory of leadership such

differences exists by virtue of fact that Likert’s theory goes beyond the mere

recognition of traits as the guiding principle for leadership.

Inherent in Likert’s theory on leadership behaviour is the notion that organization

do operate as bureaucracies. The very fact that he gives credence to hierarchical

structure of management where communication is either top down or bottom up or

both ways, and decisions resting with final authority, are aspects of bureaucratic

premise which can be construed as integrated into his arguments of leadership based

on behaviour. For example, Likert advocated vesting authority in creative leaders

with the interpersonal skills and ability to achieve organizational goals by ensuring

employees are committed to these goals and where such goals are achieved due

rewards must be given (Wren, 2005).

Where, leadership based by behaviour differs from bureaucratic leadership,

however, is found in Likert’s principle of supportive leadership. “The principle of

supportive leadership means that a leader must ensure each member of the

organization view the experience as supportive and that one builds and maintains a

sense of personal worth and importance”(Wren,2005).

There are also a number of similarities between Likert’s theory on leadership and

those delineated by Mary Parker Follett. One such similarity is found within the

principles of participative leadership. Like, Follett, Likert advocated unity within the

organization. He argued that the actions of the individual and outcomes must be in

congruence with the organization. In other words, the organization and the

individual must one and in this regard, the development and recognition of a system

where the actions of the organization is a direct outcome of the actions of the

individual, and the action of the individual is a direct outcome of the action of the

organization. (Pugh & Hinings, 1981). To this end, Likert’s systems 4 and 5 mirror

many of the thoughts presented by Follett (Wren, 2005).

Scholars, however, argue that even thought there are obvious similarities between

the theories of Likert and Follett, Likert’s would be viewed as more established in

that the principles he advocated were actually tested within various organizational

setting. Follett’s ideas, one the other hand, are regarded as mere theoretical

underpinnings of what should constitute good leadership practice (Friesen&

Johnson, 1995).

Theories of leadership and how they might address contemporary issues and

challenges

The question of how trait theory might address contemporary leadership issues and

challenges are best described by Navanhandi (2006). “There should be a modern

approach to understanding the role of traits in leadership. Several key traits are not

enough to make a leader but they are pre-conditions for effective leadership” (p.43).

Cawthon (1996) argues that the trait theory of leadership is alive and well. It began

with an emphasis on identifying the qualities of great people; next it shifted to

include the impact of situations on leadership and most currently, it has shifted back

to re-emphasize the critical role of traits in effective leadership (Northhouse, 2004).

Further, the recent rise in popularity of transformational leadership dictates that

leaders do need such traits as delineated by Navanhandi (2006) in order to augment

their capacity to lead today’s organizations. Given this premise, those responsible for

leading and managing organizations are now engaging transformational techniques.

The effectiveness of such engagement, however, is dependent on how far there is the

general belief that traits are valuable components which should be considered in the

organization process (Rost, 1991).

The basic assumption of the bureaucratic theory of leadership is that the boss knows

best and with every thing else this model of leadership is fraught with numerous

short comings. For example, the fitting of people into predefined jobs descriptions

tended to alienate them from their work, encouraged a one-way-top down

communication pattern, and discouraged learning activities (Clawson, 2000). This

means that the problem of bureaucratic leadership looms large for many

organizations, “especially North American and European firms as they wrestle with

the underlying principles, technological breakthroughs, and ferocious competition in

a new emerging paradigm” (, p.21). Such a situation begs the question of how might

the bureaucratic model address contemporary leadership issues and challenges.

Much of the theoretical perspectives which are inherent in the bureaucratic theory of

leadership still have implications for leadership and management as we know it

today. Breaking down jobs into well defined tasks, selecting managers on the basis of

their qualifications and experience, enacting formal rules and procedures to ensure

uniformity and discipline along with applying rules and control uniformly and

impersonally are all aspects of the theory which when applied effectively can have

lasting impact on organizational development and prosperity. For, example, formal

rules and procedures set the tone for conflict resolution, while systems of control

ensure operational efficiency (Scott, 2005).

During the early Social Person Era, at a time when managers believed that workers

should be seen and not heard, Follett’s theory of employees as valuable assets with

the ability to add greatly to their work if their ideas and complaints were listened to,

were not welcomed (Coye and James (2005). However, in today’s organizations

Follett’s thoughts have implications for a number of issues arising from the

leadership and management process. For example, on the issue of coordination,

many organizations promote communication across the status quo. The process is

now both horizontal and vertical as leaders and managers recognize the inherent

benefits of direct contact with their subordinates, regardless of the position they hold

within the organization.

Also the importance of human interrelationship as a driving force of organizational

change and longevity has gained much recognition. More specifically, Follett’s ideas

on integration herald modern methods of conflict resolution (Bartol and Martin,

1998) and it generally believed that for contemporary organizations, Follett’s theories

on leadership can have even greater impact on such issues as communication,

conflict resolution and management and worker negotiations if they are adequately

considered and put into practice. In the long run, organizations can learn from

Follett’s preference for constructive conflict to compromise and her belief that

employees should have a voice in how things are done, only if they share the

responsibility (Harrington, 1999).

Likert’s theory continues to be of significant value to today’s management and

leadership practices. For contemporary organizations the Likert’s scale is a valuable

tool for research and analysis of information pertaining to specific business

situations.

Additionally, the business which is profit oriented and has the concern for its human

resources as underpinning its philosophy and practice is likely to adopt the system 4

style of leadership. According to Likert (1977), all organizations should adopt the

principles of system 4. This is not to say, however, that the other styles of leadership

should be totally disregarded as each system must be assessed for the contributions it

can bring to organizational efficiency (Likert, 1977).

In practice, If Likert’s system 4 leadership theory is to be effectively applied to

today’s organizations, then the barometer for a measure of organizational

effectiveness must be defined by its ability to foster productive and supportive work

groups who must be encouraged commit to achieving the goals set out by the

organization. This means, that the practice of motivating employees to meet targets

must be driven by contemporary leadership techniques and principles. Employees

must be viewed and respected for the worth and diversity they bring to the

organization and this must be an integral part of the organization’s culture.

In the final analysis, “The most ingenious corporate structure means nothing unless

someone leads and manages it well” (Herrington, 1999, p.152). This means that issues

of leadership and its implications for personal and organizational efficiency and

effectiveness will forever pervade. For as long as there are shifting paradigms with

regard to how organizations should be led and managed, there will always be a

search for the best way to lead.

History has taught us, however, that there is no one best way to ensure effective

leadership because every organization is unique, every group of people is different

and every manager or leader has the arduous task of determining what style or

model of leadership is most effective under the situation.

Leadership therefore, is not static, it is ever changing and as time changes, managers,

leaders and researchers will continue to take sides and denounce each other (Scott,

2005). Irrespective of the outcome, the search for the best way to lead an organization

will continue. This means that leadership models and theories will always propel

organizations to seek the best course for lasting efficiency.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Bartol and Martin (1998). Management (3rd edition). New York: Irwin

McGraw Hill Companies.

2. Clawson, J, G. (2004). Level three leadership: Getting below the surface (3rd edition).

New York: Prentice Hall

3. Friensen, M & Johnson, J.A (1995). The success paradigms: Evolution of

management, administrative and leadership theories. Westport, CT: Quorun Books.

4. Martin, M & Chemers, S (1997). An Integrative theory of leadership. NJ: Laurence

Erlbaum Associates.

5. Navahandi, A. (2006). The art and science of leadership (4th Edition). NJ: Pearson

Education.

6. Rost,J.(1991). Leadership for the 21st century. New York: NY: Greenwood

Publishing Group

7. Wren,D,A.(2005). The history of management thought (5th Edition). N.J: John

Wiley and Sons, Inc.

8. Borgatta,E, Bales, R and Couch, A (2001). Some findings relevant to the great

man theory of leadership. American Sociological Review 19(6), 755-759.

Retrieved on 13th, September, 2008 from proquest database.

9. Harrington, A, F. (1999). The big idea. Fortune 140(10), 152-154. Retrieved

June 13th September, 2008 from EBSOChost database.

10. Leadersh Cawthon,D (1996). The Great Man Theory Revisited. Business

Horizons 39(3). Retrieved on 10th September, 2008, from EBSCOhost database.

11. Scott, J (2005). A Brief History of Management: The Concise Handbook of

Management 2(17). Retrieved July 8th, 2008 from EBSCOhost database.

12. Leadership: An overview (2005), Journal of Managerial Psychology, 12(7), 435-

437. Retrieved July 11, 2008, from EBSCOhost database.

SMC University is a truly global University, providing executive

education aimed at the working professional. Supported by our

centers in Europe and Latin America, as well as our partner

network in the Middle East and Asia, we assist you in creating

locally professional solutions

أَلَمْ تَرَ أَنَّ اللَّهَ يُسَبِّحُ لَهُ مَنْ فِي السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالأرْضِ وَالطَّيْرُ صَافَّاتٍ كُلٌّ قَدْ عَلِمَ صَلاتَهُ وَتَسْبِيحَهُ وَاللَّهُ عَلِيمٌ بِمَا يَفْعَلُونَ Tidakkah kamu tahu bahwasanya Allah: kepada-Nya bertasbih apa yang di langit dan di bumi dan (juga) burung dengan mengembangkan sayapnya. Masing-masing telah mengetahui (cara) solat dan tasbihnya, dan Allah Amat Mengetahui apa yang mereka kerjakan. an-Nur:41

Tazkirah

Sami Yusuf_try not to cry

mu'allim Muhammad Rasulullah Sallallahu alaihi waSalam

ummi_mak_mother_ibu_Sami Yusuf

zikir Tok Guru Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat Mu'allimul Mursyidi

syeikh masyari afasi

ruang rindu

song

Arisu Rozah

Usia 40

Mudah mudahan diluaskan rezeki anugerah Allah

usia 40 tahun

UPM

Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

pemakaian serban semsa menunaikan solat_InsyaAllah ada sawaaban anugerah Allah

Rempuh halangan

Abah_menyokong kuat oengajian Ijazah UPM

usia 39 tahun

usia 23 tahun_UPM

An_Namiru

Ijazah Pengurusan Hutan UPM

General Lumber_Nik Mahmud Nik Hasan

Chengal

Tauliah

Semasa tugas dgn general lumber

PALAPES UPM

UPM

Rumah yang lawa

Muhammad_Abdullah CD

semasa bermukim di Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

Ijazah

air terjun

Borneo land

GREEN PEACE

GREEN PEACE

Kelang

Ahlul Bayti_ Sayid Alawi Al Maliki

Asadu_ Tenang serta Berani

atTiflatul Falasthiniin

Sayid Muhammad Ahlul Bayt keturunan Rasulullah

AnNamiru_SAFARI_Kembara

AnNamiru_resting

Hamas

sabaha anNamiru fil nahri

Namir sedang membersih

Tok Guru Mualimul_Mursyid

An_Namiru

.jpg)

Namir_istirehat

.jpg)

SaaRa AnNamiru fil_Midan

.jpg)

Renungan Sang Harimau_Sabaha AnNamiru

.jpg)

Syaraba AnNamiru Ma_A

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNimru ma_A waladuha

Namir fil_Ghabi (sebut Robi...

Namir

AdDubbu_Beruang di hutan

Amu Syahidan Wa La Tuba lil_A'duwwi

AsSyahid

Namir

Tangkas

najwa dan irah

sungai

najwa

najwa

Kaabatul musyarrafah

unta

Jabal Rahmah

masjid nabawi

masjid quba

dr.eg

najwa dan hadhirah

along[macho]

![along[macho]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjuMi7D33CmR0_KXrCW2XigfLcUuQurcvtqOS139ncCwEzCyB-jUopk7QK7anADIenJEm2S0N6gAY1ubnACYXewgiAsI3rBjnLTawM39alLL-rEopOoVqn0w5WpLhPJH3hrXNtchEhgtyaI/s240/P7150023.JPG)

harissa dan hadhirah

adik beradik

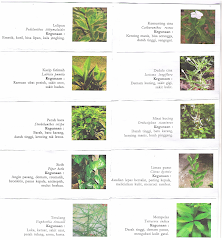

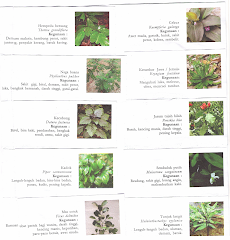

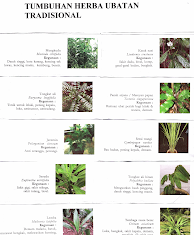

Tongkat Ali

Tongkat Ali

herba kacip Fatimah

herba Kacip Fatimah

hempedu beruang

hempedu beruang

hempedu bumi

hempedu bumi

herba misai kucing

herba misai kucing

herba tongkat Ali

.png)

Tongkat Ali

Ulama'

Ulama'

kapal terbang milik kerajaan negara ini yang dipakai pemimpin negara

kapal terbang

Adakah Insan ini Syahid

Syahid

Tok Ayah Haji Ismail

Saifuddin bersama Zakaria

Dinner....

Sukacita Kedatangan Tetamu

Pengikut

Kalimah Yang Baik

Ubi Jaga

Ubi Jaga

Arkib Blog

Burung Lang Rajawali

Chinese Sparrowhawk

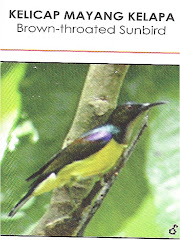

Kelicap Mayang Kelapa

Brown-Throated Sunbird

Kopiah

Pokok Damar Minyak

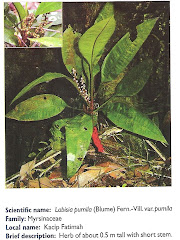

Kacip Fatimah

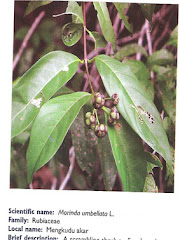

Mengkudu Akar