Leadership

Millward

According to Bryman (1996) as cited in Millward notes, however, that most researchers would not argue with a definition of leadership as the process (act) of influencing the activities of an organized group in its efforts towards goal setting and goal achievement’ (Stogdill, 1950:3 as cited in Millward). The influence process is inextricably linked with groups and the group process. In the early stages of leadership research, the ability to lead was attributed to distinctive traits (so-called ‘great man’ theory). However, a comprehensive and landmark review by Stogdill (1948) as cited in Millward concluded that there was no evidence for this claim, and research took another turn. In particular, the focus shifted towards understanding how exactly leaders behave, and to linking different group processes with different styles of behaviour.

Leadership Style

There are many different models of leadership style, but common to all is the assumption that leadership behaviour can be described in two main ways: task-oriented and relationship-oriented. The task style is oriented to managing task accomplishment (where the leader defines clearly and closely what subordinates should be doing and how, and actively schedukes work for them), whilst the relationship style is oriented to managing the interpersonal relations to group members (by demonstrating concern about subordinates as people, responsiveness to subordinate needs and the promotion of team spirit and cohesion).

Other terms have been used to differentiate between these two distinc sets of orientation, including ‘initiating structure’ versus ‘consideration’ (Fleishman, 1953 as cited in Millward), ‘production-oriented’ versus people-oriented’ (Blake & Mouton, 1964 as cited in Millward., ‘production-centred’ versus ‘employee-centred (Likert,1967), ‘task emphasis’ versus relations emphasis’ (Fiedler, 1967 as cited in Millward) and ‘performance concern’ versus ‘maintenance concern’ (Misumi, 1985 as cited in Millward)

The ‘initiating structure/ consideration’ distinction has had a major impact on leadership theory and research since the 1950s. It forms the basis of many leadership measures, for instance the Supervisory Behaviour Description Questionnaire (Fleish, 1953 as cuted in Millward)- a vehicle for asking subordinates how they think should behave as a supervisor- and the Leader Behaviour Description Questionnaire (LBDQ); (Fleisman, 1953 as cited in Millward) probably the most frequently employed measure of leadership. (pg234)

Swedlik pg 395

Some highly specialized Q-sorts include the Leadership Q-Test (Cassel,1958 as cited in Swedlik et al) and the Tyler Vocational Classification System (Tyler, 1961 as cited in Swedlik et al)

Aamodt,2010

Pg 438

Personal Characteristics Associated with Leadership

In the last 100 years, many attempts have been made to identify the personal characteristics associated with leader emergence and leader performance.

Leader Emergence

Leader emergence is the idea that people who become leaders possess traits or characteristic different from people who do not become leaders. That is, people who become leaders, such as Barrack H. Obama and CEOs Carly Fiorina and Michael Dell, share traits that your neighbor or a food preparer at McDonald’s does not. If we use your school as an example, we would predict that the students in your student government would be different from students who do not participate in leadership activities. In fact, research indicates that to some extent, people are “born’ with a desire to lead or not lead, as somewhere between 17% (Ilies, Gerhardt,&Le, 2004 as cited in Aamodt) and 30% (Arvey, Rotundo, Johnson, Zhang,&McGue,2006 as cited in Aamodt) of leader emergence has a genetic basis (Ilies et al.,2004 as cited in Aamodt)

Does that mean that there is a “leadership gene” that influences leader emergence? Probably not. Instead we inherit certain traits and abilities that might influence our decision to seek leadership. Though early reviews of the literature suggested that the relationship between traits and leader emergence is not very strong, as shown in Table 12.1, more recenr reviews suggest that

1. People high in openness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, and low in neuroticism are more likely to emergence as leaders than their counterparts (Judge, Bono, Ilies & Gerhardtm2002 as cited in Aamodt 2010).

2. High self-monitors (people who adapt their behavior to the social situation) emerge as leaders more often than low self-monitors (Dayb & Schleicher, 2006; Day,Schleicher,Unckless, & Hiller, 2002 as cited in Aamodt 2010)

3. More intelligent people are more likely to emerge as leaders than are less intelligent people (Judge, Colbert, & Ilies, 2004 as cited in Aamodt 2010)

4. Looking at patterns of abilities and personality traits is more useful than looking at individual abilities and traits (Foti & Hauenstein, 2007 as cited in Aamodt 2010)

Table 12.1 Summary of Meta-Analysis od Leader Emergence and Performance…pg 440_Aamodt

It is especially perplexing that some of the early reviews concluded that specific trait are seldom related to leader emergence because both anecdotal evidence and research suggest that leadership behavior has some stability (Law,1996 as cited in Aamodt 2010) To illustrate this point, think of a friend you consider to be a leader. In allprobability, that person is ;eader in many situations. That is, he might influence a group of friends about what movie to see, make decision about what time everyone should meet for dinner, and “take charge” when playing sports

Conversely, you probably have a friend who has never assumed a leadership role in his life. Thus, it appears that some people consistently emerge as leaders in a variety of situations, whereas others never emerge as leaders.

Perhaps one explaianation for the lack of agreement on a list of traits consistently related to leader emergence is that the motivation to mlead is more complex than originally thought. In a study using a large international sample, Chan and Drasgow (2001) as cited in Aamodt found that the motivation to lead has three aspects (factors):

Affective identity, noncalculative, and social-normative. Peole with an affective identity motivation become leaders because they enjoy being in charge and leading others. Of the three leadership motivation factors, people scoring high on this one tend to have the most leadership experience and are rated by others as having high leadership potential. Those with a noncalculative motivation seek leadership position when they perceive that such positions will result in personal gain.

For example, becoming a leader may result in an increase in status or in pay. People with a social-normative motivation become leaders out of a sense of duty. For example, a member of the Kiwanis Club might agree to be the next president because it is “his turn”, or a faculty member might agree to chair a committee out of a sense of commitment to the university

Individuals with high leadership motivation tend to obtain leadership experience and have confidence in their leadership skills (Chan & Drasgow, 2001 as cited in Aamodt 2010). Therefor after researching the extent to which leadership is consistent across life, it makes sense that Bruce (1997) as cited in Aamodt (2010) concluded that the best way to select a chief executive officer (CEO) is ti look for leadership qualities (e.g., risk taking,innovation, vision) and success early in person’s career. As support for his proposition, Bruce cites the following examples:

1. Harry Gray, the former chair and CEO of United Technologies, demonstrated vision, risk taking, and innovation as early as the second job in his career.

2. Ray Tower, former president of FMC Corporation, went way beyond his job description as a salesperson in his first job to create a novel sales training program. Tower continued to push his idea despite upper management’s initial lack of interest.

3. Lee Iacocca, known for his heroics at Ford and Chrysler, pioneered the concept of new car financing. His idea of purchasing a 1956 Ford for monthly payments of $56 (“Buy a ’56 for $56”) moved his sales division from last in the country to first. What is most interesting abaout this success is that Iacocca didn’t even have the authority to implement his plan-but he did it anyway.

The role of gender in leader emergence is complex. Meta-analysis indicate that men and women emerge as leaders equally often in leaderless group discussions (Benjamin, 1996 as cited in aamodt 2010), men emerge as leaders more often in short-term groups and group carrying out tasks with low social interaction (Eagly & Karau, 1991 as cited in Aamodt 2010), andwomen emerge as leaders more often in groups involving high social interaction (Eagly & Karau, 1991 as cited in Aamodt 2010)….pg 441

Leader Performance

In contrast to leader emergence, which deals with the likelihood that a person will become a leader, leader performance involves the idea that leaders who perform well possess certain characteristics that poorly performing leaders do not. For example, an excellent leader might be intelligent, assertive, friendly and independent, whereas a poor leader might be shy, aloof, and calm. Research on the relationship between personal characteristics and leader performance has concentrated on three areas: traits, needs and orientation.

Traits

As shown in Table 12.1, a mete- analysis by Judge et al (2002) as cited in Aamodt 2010 found that extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness were positively related to leader performance. A meta-analysis by Youngjohn and Woehr (2001) as cited in Aamodt also found that management, decision making, and oral-communication skills were highly correlated with leadership effectiveness

As was the case with leader emergence, high self-monitors tend to be better leaders than do low self-monitors (Day & Schleicher, 2006; Day et al., 2002 as cited in Amodt 2010). The concept of self monitoring is especially interesting, as it focuses on what leaders do as opposed to what they are. For example, a high self-monitoring leader may possess the trait of shyness and not truly want to communicate with other people.

She knows, however, that talking to others is an important part of her job, so she says hello to her employees when she arrives at work, and at least once a day stops and talks with each employee. Thus, our leader has the trait of shyness but adapts her outward behavior to appear to be outgoing abd confident. To determine your level of self-monitoring, complete Section A in Exercise 12.2 in your workbook.

An intersesting extension of the trait theory of leader performance suggests that certain traits are necessary requirements for leadership excellence is a function of the right person being in the right place at the right time. The fact that one person with certain traits becomes an excellent leader while another with the same traits flounders may be no more than the result of timing and chance

For example, Lyndon Johnson and Martin Luther King, Jr were considered successful leaders because of their strong influence on improving civil rights. Other people prior to the 1990s had had same thoughts, ambitions, and skills as King and Johnson, yet they had not become successful civil rights leaders, perhaps because the time had not been right.

Cognitive Ability

A mete-analysis of 151 studies by Judge et al. (2004) as cited in Aamodt 2010 found a moderate but significant correlation (r=.17) between cognitive ability and leadership performance. The mete-analysis further discovered that cognitive ability is most important when the leader is not distracted by stressful situations and when the leader uses a more directive leadership style. In studies investigating the performance of united states Presidents, it was found that the presidents rates by historians as being the most successful were smart and open to experience, had high goals, and interestingly had the ability to bend the truth (Dingfelder, 2004; Rubenzer & Faschinbauer,2004) as cited in aamodt 2010 has expanded on the omportance of cognitive ability by theorizing that the key to effective leadership is the synthesis of three variables:wisdom, intelligence (academic and practical), and creativity. Pg 443

Doyle

Pg 23

Issues include the factors which influence the amount of effort expended at work, the influence of job satisfaction on levels of performance and organizational commitment, the processes thet underly group behaviour and decision making, and the exercise of power and influence in organizations. Also of interest is the nature of leadership and followership, and the management of organizational change.

Pg 69

So far we have largely been talking about top management. The focus on top management has also led to a renewed interest in the process of leadership both within senior teams and at every level within the organization (see, e.g., Schruijer, 1992; Sparrow, 1994 as cited in Doyle 2002). Shell for instance, encapsulates its vision as “Leaders leading Leaders” (Steel, 1997 as cited in Doyle 2002). Much is made of the ability to formulate and communicate vision. From ideas such as this, Bass and his colleagues proposed the concept of transformational leadership, in which the leader’s ability to inspire and empower followers and to create a belief in the attainability of the vision are stressed (Bass,1999;Bass & Avolio, 1990 as cited in Doyle 2002). Many culture change programmes begin with leadership development of senior managers, which then spreads more widely throughout the organization. Schruijer and Vansina (1999a, 1999b) as cited in Doyle 2002 edit and provide a commentary on a fascinating collection of papers that consider the role of leadership in organizational change. They raise a number of important and difficult questions concerning top-level leadership in organizations, including the extent to which one should focus on the individual qualities of the leader or on the incredibly complex set of relationships between leaders and followers. For instance, followers may exhibit dependence on, trust in, loyalty, and commitment to the leader but nevertheless aspire to an complete strongly for his or her job (Berg, 1998 as cited in Doyle 2002). Schruijer and Vansina conclude that one thing characterizing successful leaders in today’s turbulent business environment is their capacity to collaborate with diverse groups and stakeholders to achieve strategic objectives. The dynamics of this kind of shared leadership are illuminated by the work of De Vries, Roe, and Tailieu (1999) as cited in Doyle 2002 and Rijaman (1999) as cited in Doyle 2002, who both emphasize a “follower-centred” approach. Alimo-Metcalfe and Alban-Matcalfe (2000) as cited in Doyle 2002 are also considering the influence of “nearby” leaders rather than top management and conceptualizing the former as “servants” to their followers. However, as Bass (1999) as cited in doyle 2002 and others have stressed, transformational leadership is needed as well as more mundane management that organizes and coordinates work and provides the structure for implementing the fine detail of change.

Pg 71

أَلَمْ تَرَ أَنَّ اللَّهَ يُسَبِّحُ لَهُ مَنْ فِي السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالأرْضِ وَالطَّيْرُ صَافَّاتٍ كُلٌّ قَدْ عَلِمَ صَلاتَهُ وَتَسْبِيحَهُ وَاللَّهُ عَلِيمٌ بِمَا يَفْعَلُونَ Tidakkah kamu tahu bahwasanya Allah: kepada-Nya bertasbih apa yang di langit dan di bumi dan (juga) burung dengan mengembangkan sayapnya. Masing-masing telah mengetahui (cara) solat dan tasbihnya, dan Allah Amat Mengetahui apa yang mereka kerjakan. an-Nur:41

Tazkirah

Sami Yusuf_try not to cry

mu'allim Muhammad Rasulullah Sallallahu alaihi waSalam

ummi_mak_mother_ibu_Sami Yusuf

zikir Tok Guru Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat Mu'allimul Mursyidi

syeikh masyari afasi

ruang rindu

song

Arisu Rozah

Usia 40

Mudah mudahan diluaskan rezeki anugerah Allah

usia 40 tahun

UPM

Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

pemakaian serban semsa menunaikan solat_InsyaAllah ada sawaaban anugerah Allah

Rempuh halangan

Abah_menyokong kuat oengajian Ijazah UPM

usia 39 tahun

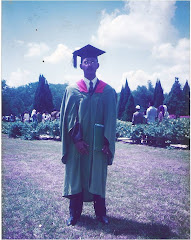

usia 23 tahun_UPM

An_Namiru

Ijazah Pengurusan Hutan UPM

General Lumber_Nik Mahmud Nik Hasan

Chengal

Tauliah

Semasa tugas dgn general lumber

PALAPES UPM

UPM

Rumah yang lawa

Muhammad_Abdullah CD

semasa bermukim di Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

Ijazah

air terjun

Borneo land

GREEN PEACE

GREEN PEACE

Kelang

Ahlul Bayti_ Sayid Alawi Al Maliki

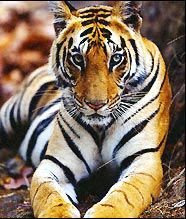

Asadu_ Tenang serta Berani

atTiflatul Falasthiniin

Sayid Muhammad Ahlul Bayt keturunan Rasulullah

AnNamiru_SAFARI_Kembara

AnNamiru_resting

Hamas

sabaha anNamiru fil nahri

Namir sedang membersih

Tok Guru Mualimul_Mursyid

An_Namiru

.jpg)

Namir_istirehat

.jpg)

SaaRa AnNamiru fil_Midan

.jpg)

Renungan Sang Harimau_Sabaha AnNamiru

.jpg)

Syaraba AnNamiru Ma_A

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNimru ma_A waladuha

Namir fil_Ghabi (sebut Robi...

Namir

AdDubbu_Beruang di hutan

Amu Syahidan Wa La Tuba lil_A'duwwi

AsSyahid

Namir

Tangkas

najwa dan irah

sungai

najwa

najwa

Kaabatul musyarrafah

unta

Jabal Rahmah

masjid nabawi

masjid quba

dr.eg

najwa dan hadhirah

along[macho]

![along[macho]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjuMi7D33CmR0_KXrCW2XigfLcUuQurcvtqOS139ncCwEzCyB-jUopk7QK7anADIenJEm2S0N6gAY1ubnACYXewgiAsI3rBjnLTawM39alLL-rEopOoVqn0w5WpLhPJH3hrXNtchEhgtyaI/s240/P7150023.JPG)

harissa dan hadhirah

adik beradik

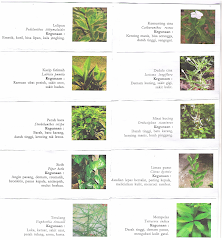

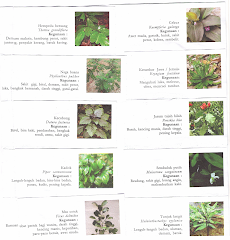

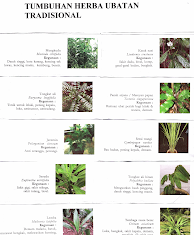

Tongkat Ali

Tongkat Ali

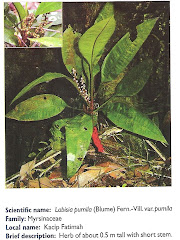

herba kacip Fatimah

herba Kacip Fatimah

hempedu beruang

hempedu beruang

hempedu bumi

hempedu bumi

herba misai kucing

herba misai kucing

herba tongkat Ali

.png)

Tongkat Ali

Ulama'

Ulama'

kapal terbang milik kerajaan negara ini yang dipakai pemimpin negara

kapal terbang

Adakah Insan ini Syahid

Syahid

Tok Ayah Haji Ismail

Saifuddin bersama Zakaria

Dinner....

Sukacita Kedatangan Tetamu

Pengikut

Kalimah Yang Baik

Ubi Jaga

Ubi Jaga

Arkib Blog

Burung Lang Rajawali

Chinese Sparrowhawk

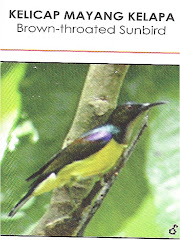

Kelicap Mayang Kelapa

Brown-Throated Sunbird

Kopiah

Pokok Damar Minyak

Kacip Fatimah

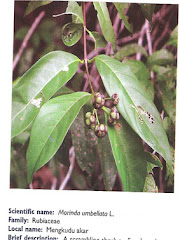

Mengkudu Akar