A new century of environmental consciousness is dawning. Under the pressures of explosive human population growth, our planet’s natural communities are shriveling rapidly. They are shrinking on all sides because of the expansion of agriculture, urbanization, damming, forest fragmentation, contaminants into water tables, road building, and even more indirect human impacts such as the invasion by exotic species and the distribution of genetic crops.1 In Nepal, ecotourists flock to hike one of the remaining wilderness regions on the planet, but these hikers have stripped the landscape bare of sticks and twigs for fuel and left trash that spoils the experience for future visitors. In the Galapagos, the burgeoning number of visitors strains these sensitive and fragile islands. The impact of these visitors, manifested by disease, fire, and theft, has altered the natural balance of the island ecosystems. In the last decade, approximately 20 of the 230 species of plants face immediate extinction, and another 10 are thought to be extinct.2 In contrast, I have witnessed the salvation of exploited tropical regions by the interests of conservation and the economy of ecotourism working collectively.

What is ecotourism?

Ecotourists learn about natural as well as cultural history.Ecotourism is loosely defined as nature-based tourist experiences, whereby visitors travel to regions for the sole purpose of appreciating their natural beauty. As early as 1965, responsible tourism was defined:3

respects local culture

optimizes benefits to local people

minimizes environmental impacts

maximizes visitor satisfaction

The first formal definition, coining the term “ecotourism,” was published in 1987: “traveling to relatively undisturbed or uncontaminated natural areas with the specific objective of studying, admiring, and enjoying the scenery and its wild plants and animals, as well as any existing cultural manifestations (both past and present) found in these areas.” 4,5 Subsequently, many other definitions have arisen.6-11

Ecotourism probably had its foundations in the ethics of conservation, but its recent surge has certainly been due to its economic benefits as developing countries begin to recognize that nature-based tourism offers a means of earning money with relatively little exploitation or extraction of resources. It is this economic incentive, perhaps more than the consciousness of human ethics, that has given rise to the global expansion of environmentally responsible tourism activities.

A variety of educational experiences is possible.The objectives of ecotourism are to provide a nature-based, environmental education experience for visitors and to manage this in a sustainable fashion. As forests become logged, as streams become polluted, and as other signs of human activity become ubiquitous, the requirements of a true ecotourism experience are increasingly difficult to fulfill. To compensate for the “invasion” of human disturbance, ecotourism has promoted the educational aspects of the experience. Examples include opportunities to work with scientists to collect field data in a remote wilderness (e.g., Earthwatch) or travel with a naturalist to learn the secrets of a tropical rain forest (e.g., Smithsonian Institution travel trips). Environmental education serves to provide information about the natural history and culture of a site; it also promotes a conservation ethic that may infuse tourists with stronger pro-environmental attitudes.

Types of ecotourism

In most cases, ecotourism follows two important principles of sustainability:12

to promote conservation of the natural ecosystems

to support local economies

Limiting visitors will lessen the impact.These underlying principles are the pillars that will provide a lasting basis for ecotourism and will also create sound economic support for the conservation of natural resources. They provide ultimately competitive reasons for the expansion of ecotourism above and beyond other types of leisure activities. A challenge arises, however, when ecotourism becomes successful, in the sense that too many tourists destroy the reason for success. In the case of ecotourism, as different from many other marketed products in our Western economy, economic success is a matter of limiting supply no matter how much the demand.

Trips range from soft to hard ecotourism.In a decade, this type of recreation has burgeoned to include many different intensities and levels of experiences, ranging from extreme rock climbing to nature journaling at a luxury mountain resort.5 There is soft versus hard ecotourism, alluding to the physical rigor of the conditions experienced by the visitors. Trekking on the Inca Trail is much more rigorous than taking a train or bus to Machu Picchu and staying in the lodge. There are arguments over the natural versus unnatural versions of ecotourism; in other words, proponents of ecotourism believe that humans are part of nature and that their impact is part of the natural process, whereas critics of ecotourism maintain that people simply should not visit natural areas because they invariably degrade them.

Ecotourism in, say, the Grand Canyon can be

passive, such as viewing the canyon

active, such as rafting down the Colorado River

exploitive, such as staying in the lodge on the rim of the canyon

Ecotourism can also be

mass tourism, where optimization of income is the most important factor, and expanding programs are measures of success

alternative tourism, where environmental sustainability and limiting the number of tourists are the most important measures of success

Increasing popularity of ecotourism

Organized tours account for over $2 trillion globally.Since Thomas Cook began the world’s first travel agency in 1841,13 the number of people who enjoy organized travel has continued to increase. Today, an estimated 1.6 billion people from all cultures and all walks of life participate in different kinds of tourism, spending over $2 trillion.3 On a global scale, ecotourism is growing because of its international appeal. Costs have decreased. Mass media have also popularized the notion of nature travel, especially through television networks such as National Geographic, Discovery, and Animal Planet and associated magazines or videos. Tourists recognize that if they travel with sensitivity to the environment, they will not only contribute to conservation but also become educated about a new habitat, country, or culture.

Some tour operators hold certificates of authenticity.Some countries have established eco-labels or certification for authentic nature-based tourism, such as Green Globe (international) or Committed to Green (Europe). This enhances the credibility of an experience for tourists who come to know specific reputable names. In contrast, some events in certain countries may impact tourism negatively, such as the recent bombing in Bali or the reputation of drug trafficking in Colombia. Exotic countries with stable governments, such as Belize, are the true beneficiaries of ecotourism and stand in contrast to some of their neighbors who cannot offer the same reliability of ecotourist experience. As politics continue to affect our ability (or lack thereof) to travel, regional tourism will be significantly impacted by government policies related to stability.

Global impacts on forest conservation

The following are three case studies that have assisted forest conservation:

aerial tram in Costa Rica

canopy walkway in Savai’i, Western Samoa

canopy walkway and tower in Florida, USA

The Rain Forest Aerial tram, in Costa Rica

Many people see Costa Rica as a shining example of conservation, but it is neither better nor worse than many countries.14

Costa Rica is losing its forests at an alarming rate.Banana cultivators, lumber harvesters, and farmers are stripping the lowlands of rainforest trees.

Costa Rica has proportionally less rain forest left than many other tropical countries. In fact, only a few islands of relatively untouched lowland Caribbean rain forest remain. Less than 10 percent of Costa Rica’s forests are national parks.

Both the national park service and FUNDECOR, a nonprofit organization devoted to the conservation of national parks, acknowledge there is not enough money to protect the national parks and their boundaries from encroachment and destruction.14

At the current rate, forests outside of park lands will only last 5 to 10 years in this country that supposedly represents the bastion of conservation in Latin America.10

An aerial tram was built for scientific research.The aerial tram had its origin in Don Perry’s efforts to devise tree-climbing techniques for scientific investigation. After experiencing the limitations of single-rope techniques, he realized that to study the canopy effectively, researchers need a vehicle for access. In 1983, Perry teamed up with the engineering expert John Williams, and together they created the Automated Web for Canopy Exploration (AWCE) at Rara Avis in Costa Rica. This vehicle can carry scientists from ground level to above the treetops through approximately 22,000 cubic meters of forest.

After the AWCE was built, Perry and Williams designed the Rain Forest Aerial Tram, which was located closer to San Jose and more suitable for ecotourists.

A tram was then developed for ecotourism.The tram proved very profitable.Another ecotourism project was begun in Savai’i.It occupies a 1.3 km route through pristine lowland rain forest.

Twenty-four cars each hold up to six people, including one guide.

The cars are attached to a cable that rotates around two end stations; the system is actually a converted ski lift.

Approximately 70 people per hour are carried through the canopy, representing approximately 40,000 visitors per year.10

According to Perry,14 the site operated with enough profit to grant local school groups free admission. Displays at the site educate visitors about the tropical rain forest canopy and its inhabitants. This site is the first of its type worldwide, but more aerial trams and canopy walkways are now in operation in other countries such as Australia, Peru, and the United States.

Canopy walkway in Savai’i, Western Samoa

Paul Cox, internationally recognized ethnobotanist, has worked for many decades on the islands of the South Pacific. In particular, Cox spent many years in the village of Falealupo on the island of Savai’i. He befriended the village healer, a wonderful botanist named Pele, who taught him how Samoans use their local plants as an apothecary. In the early 1990s, Cox and I worked on an ecotourism project that we hope serves as a model for the application of ecotourism to conservation in the South Pacific.

The forest provides all the needs of the village—spiritual, economic, biological— and had done so for many generations.

The island’s forests have supported locals for generations.Island ecosystems are chance events because the combination of species collects by means of drift, wind, and bird dispersal. Savai’i has unusual diversity for an island ecosystem.

The villagers depend on the forest for everything: food, clothing, medicines, and homes.

The forests even nurture island ancestors whose spirits are embodied in the flying foxes (Pteropus samoensis) that live and breed within the forest.

The locals considered selling logging rights.The village was offered a large sum of money in exchange for logging rights to its forest. The chiefs were not happy about the proposal but they needed to pay for reconstruction after a devastating monsoon. Paul Cox had a novel suggestion for the chiefs: What about developing ecotourism to bring in a cash economy while managing the forest sustainably? He suggested a canopy walkway to attract tourists, who would in turn pay for the privilege of walking in the treetops of Samoa. A loan was obtained, and some generous seed money was provided from Seacology Foundation in the United States.

Scientists offered an alternative: a canopy walkway.The economy was boosted and forest sustainability maintained.Two research associates and I, representing Canopy Construction Associates, joined Cox for a reconnaissance trip to determine the feasibility of an ecotourism walkway in Falealupo. After many hours of discussion with locals, it was agreed that an enormous emergent fig would represent the center of all construction, from which bridges spanning the forest could be built to adjacent trees. We measured and mapped the area to gather all of the pertinent information required to construct the canopy walkway several thousand miles away. One of the drawbacks to construction in developing countries is that it is impossible to ask for new measurements or to get something checked in the field. In this case, we needed to estimate carefully all supplies and equipment coming from the United States.

Florida offers a 24-hour canopy walkway.The walkway is accessible to the handicapped.Canopy Construction Associates handed the job over to another, smaller construction team, Kevin Jordan and Stephanie Hughes, who were willing to build a simple platform around the fig tree and take on the risks of weather, financial liability, and lost or damaged equipment. The end result was a walkway that contributes to the economy of the village of Falealupo in a sustainable fashion and ensures the conservation of the forest for future generations.

Canopy walkway and tower in Florida, USA

In the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens in Sarasota, Florida, a handicapped-accessible canopy walkway was constructed in 1998; and in Myakka River State Park just outside Sarasota, a public canopy walkway and tower, open 24 hours a day to the public, opened in June 2000. Both of these projects came from public funding and awareness of the importance of bringing people into forests.

The botanical gardens walkway was the inspiration of a local builder, Michael Walker and Associates. Walker modeled his construction after the children’s book, The Most Beautiful Roof in the World by Kathryn Lasky.15 Walker carefully built a child-friendly structure according to Americans with Disabilities Act regulations, so that anyone—in a wheelchair, with a stroller, or with a walker—can enjoy the treetops. Delegates in wheelchairs cut the ribbon, officially opening the walkway. Many tears of joy were shed by these wheelchair-bound adults who had always dreamed of climbing a tree.

Visits to the state forest increased over 40 percent.At Myakka River State Park, I worked with a community leadership team to design and raise money for a public canopy walkway. The Myakka walkway

spans 100 feet and includes a 70-foot tower that rises above the canopy

has increased visitorship to the park by 42 percent in three years

has become exemplary throughout Florida and beyond.

People from all over the country have learned about forests from the interpretive signage along the walkway. More importantly, they have also gained an appreciation for the beauty and value of forests in our daily lives.

Public-private partnerships can work to conserve nature.Over the past five years, Sarasota County has continued to purchase and add parcels of environmentally sensitive lands to their system as part of a long-term vision of developing recreation and nature-based tourism in some of these natural lands. This unique land acquisition scheme, coupled with innovative public-private partnerships to operate ecotourism activities, is still in its infancy, but it is destined to become a national model for bringing the public into contact with natural landscapes. Canopy walkways are just one way to engage people’s interest in these natural areas; the goal is to connect people to nature in their own back yards.

Conclusion

Sustainability remains untested because ecotourism is new.Ecotourism can help maintain what’s left of nature.Ecotourism, in partnership with research, has the potential to significantly affect forest conservation in many positive ways. The question of sustainability remains unanswered because many sites with nature-based tourism are relatively new and the long-term impacts have yet to be measured. The challenges of removing trash from remote wilderness lodges, of bringing in electricity with low-impact electric wires, or of minimizing the introduction of exotic species require the test of time to determine their success.

In the not-too-distant future, our wilderness areas will be small islands of biodiversity amidst seas of domesticated landscape. As the planet’s natural, relatively unaltered ecosystems become increasingly rare, ecotourism allows more people to see our isolated populations of wildlife, while benefiting local economies. Ecotourism has an impact on natural ecosystems, but more importantly, it offers a way to promote conservation in ecologically fragile regions.

© 2004, American Institute of Biological Sciences. Educators have permission to reprint articles for classroom use; other users, please contact editor@actionbioscience.org for reprint permission. See reprint policy.

Margaret (Meg) Dalzell Lowman, Ph.D., is currently professor of biology and environmental studies at New College, the premier honors college for the State of Florida and Ecological Consultant for Sarasota County. From 1992-2003, she served first as director of research and conservation and then as chief executive officer of Marie Selby Botanical Gardens. Prior to joining the gardens, Lowman was a professor in biology and environmental studies at Williams College, Massachusetts, where she pioneered several aspects of temperate forest canopy research and built the first canopy walkway in North America. From 1978-1989, she lived in Australia, where she taught at the University of New England and worked on canopy processes in both rain forests and dry sclerophyll forests. Lowman has authored over 80 peer-reviewed publications and 3 books. Her latest book, Life in the Treetops, received a front-page review in the New York Times Sunday Book Review. Among Lowman’s awards are a Pew Fellow nomination (1993) and the Eugene P. Odum Award for Excellence in Ecology Education from the Ecological Society of America (2002). Carolyn Shoemaker of the U.S. Department of the Interior named an asteroid after Lowman (2003). Meg received a M.Sc. in ecology from Aberdeen University (1978), and a Ph.D. in botany from the University of Sydney (1983).

أَلَمْ تَرَ أَنَّ اللَّهَ يُسَبِّحُ لَهُ مَنْ فِي السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالأرْضِ وَالطَّيْرُ صَافَّاتٍ كُلٌّ قَدْ عَلِمَ صَلاتَهُ وَتَسْبِيحَهُ وَاللَّهُ عَلِيمٌ بِمَا يَفْعَلُونَ Tidakkah kamu tahu bahwasanya Allah: kepada-Nya bertasbih apa yang di langit dan di bumi dan (juga) burung dengan mengembangkan sayapnya. Masing-masing telah mengetahui (cara) solat dan tasbihnya, dan Allah Amat Mengetahui apa yang mereka kerjakan. an-Nur:41

Tazkirah

Sami Yusuf_try not to cry

mu'allim Muhammad Rasulullah Sallallahu alaihi waSalam

ummi_mak_mother_ibu_Sami Yusuf

zikir Tok Guru Nik Abdul Aziz Nik Mat Mu'allimul Mursyidi

syeikh masyari afasi

ruang rindu

song

Arisu Rozah

Usia 40

Mudah mudahan diluaskan rezeki anugerah Allah

usia 40 tahun

UPM

Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

pemakaian serban semsa menunaikan solat_InsyaAllah ada sawaaban anugerah Allah

Rempuh halangan

Abah_menyokong kuat oengajian Ijazah UPM

usia 39 tahun

usia 23 tahun_UPM

An_Namiru

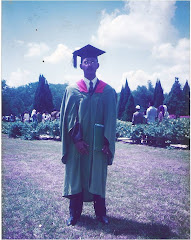

Ijazah Pengurusan Hutan UPM

General Lumber_Nik Mahmud Nik Hasan

Chengal

Tauliah

Semasa tugas dgn general lumber

PALAPES UPM

UPM

Rumah yang lawa

Muhammad_Abdullah CD

semasa bermukim di Kuatan Pahe Darul Makmur

Ijazah

air terjun

Borneo land

GREEN PEACE

GREEN PEACE

Kelang

Ahlul Bayti_ Sayid Alawi Al Maliki

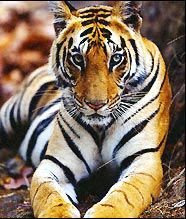

Asadu_ Tenang serta Berani

atTiflatul Falasthiniin

Sayid Muhammad Ahlul Bayt keturunan Rasulullah

AnNamiru_SAFARI_Kembara

AnNamiru_resting

Hamas

sabaha anNamiru fil nahri

Namir sedang membersih

Tok Guru Mualimul_Mursyid

An_Namiru

.jpg)

Namir_istirehat

.jpg)

SaaRa AnNamiru fil_Midan

.jpg)

Renungan Sang Harimau_Sabaha AnNamiru

.jpg)

Syaraba AnNamiru Ma_A

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNamiru_Riadhah

.jpg)

AnNimru ma_A waladuha

Namir fil_Ghabi (sebut Robi...

Namir

AdDubbu_Beruang di hutan

Amu Syahidan Wa La Tuba lil_A'duwwi

AsSyahid

Namir

Tangkas

najwa dan irah

sungai

najwa

najwa

Kaabatul musyarrafah

unta

Jabal Rahmah

masjid nabawi

masjid quba

dr.eg

najwa dan hadhirah

along[macho]

![along[macho]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjuMi7D33CmR0_KXrCW2XigfLcUuQurcvtqOS139ncCwEzCyB-jUopk7QK7anADIenJEm2S0N6gAY1ubnACYXewgiAsI3rBjnLTawM39alLL-rEopOoVqn0w5WpLhPJH3hrXNtchEhgtyaI/s240/P7150023.JPG)

harissa dan hadhirah

adik beradik

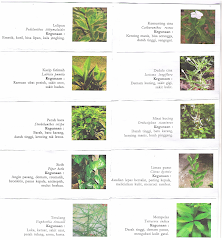

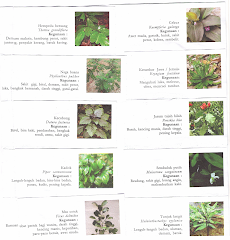

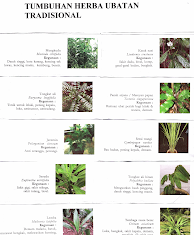

Tongkat Ali

Tongkat Ali

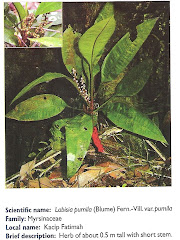

herba kacip Fatimah

herba Kacip Fatimah

hempedu beruang

hempedu beruang

hempedu bumi

hempedu bumi

herba misai kucing

herba misai kucing

herba tongkat Ali

.png)

Tongkat Ali

Ulama'

Ulama'

kapal terbang milik kerajaan negara ini yang dipakai pemimpin negara

kapal terbang

Adakah Insan ini Syahid

Syahid

Tok Ayah Haji Ismail

Saifuddin bersama Zakaria

Dinner....

Sukacita Kedatangan Tetamu

Pengikut

Kalimah Yang Baik

Ubi Jaga

Ubi Jaga

Arkib Blog

Burung Lang Rajawali

Chinese Sparrowhawk

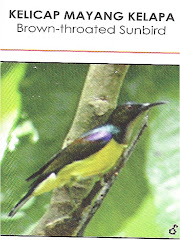

Kelicap Mayang Kelapa

Brown-Throated Sunbird

Kopiah

Pokok Damar Minyak

Kacip Fatimah

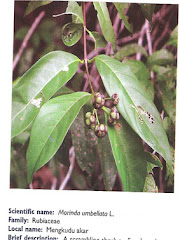

Mengkudu Akar