Al_'Aqil yatakallamu 'anil syakhsiah

AzZaki yatakallamu 'anil madhiah/qadhiah

A'_'Abqoriyyu yatakallamu 'anil FIKRAH wal ISLAH

30 April 2010

29 April 2010

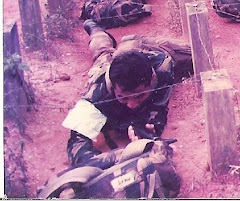

Ijazah Sains Perngurusan Hutan UPM

Alhamdulillah dapat ijzah di UPM pada 16 tahun lalu semasa usia 24 tahun

kini Alhamdulillah dapat uruskan hutan pada usia 40 tahun kini dapat dapat pengalaman menarik di hutan

abah dan mak telah menyokong pengajian ku di UPM dengan usaha dan doa mak abah ...Allhamdulillah saya apat Ijazah

kini Alhamdulillah dapat uruskan hutan pada usia 40 tahun kini dapat dapat pengalaman menarik di hutan

abah dan mak telah menyokong pengajian ku di UPM dengan usaha dan doa mak abah ...Allhamdulillah saya apat Ijazah

Logging operation impact to environment_destruction to forest stand

THE WELL-DOCUMENTED environmental impacts of logging167 are summarised below. Environmental impact assessments of logging operations in a number of different countries (Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Cameroon, for instance) clearly demonstrate that destructive logging practices using heavy machinery seriously reduce the forest's ability to carry out vital environmental and ecological functions.

Watershed Management and Soil Erosion

Forests provide a buffer to filter water and to hold soil in place. They sustain water and soil resources through recycling nutrients. In watersheds where forests are degraded or destroyed, minimum flows decrease during the dry season, leading to drought, while peak floods and soil erosion increase during

Tributary meets Melinau River, upper reaches of Baram river. Tributary water (left of picture), from preserved, non-logged and non-eroded watershed. Water from main river is cloudy with sediment from logging operations.

Flooding along the Baram River in Sarawak has increased significantly since logging began, the major floods occurring in 1979 and 1981.168 Massive floods, directly linked to excessive logging, have caused hundreds of deaths in the Philippines169 and Thailand.170

Much of the current logging carried out in Sarawak and other places is on steep lands dominated by surface materials that are highly susceptible to erosion when disturbed.171 Data collected by the Malaysian Department of Environment in 90 long-term sampling site locations within 21 river basins has detected incredibly high suspended sediment loads in most rivers and tributaries. This mainly originates from upstream soil erosion caused by the indiscriminate construction of logging roads and camps, skid trails and logging itself.172 Dr Saulei of the University of Papua New Guinea also blames the logging industry for 'accelerating erosion, weathering and humus decomposition, and leading to widespread formation of soils with low nutrient and absorptive capacities'

A skid track with severe erosion. More than a metre of topsoil has been lost and the bedrock exposed along many metres of this skid track on Isabel Island, Solomon Islands (see Kumpulan Emas, page 44).

The scale of inputs of mobilised sediment is clearly seen in this photograph where many tonnes of material are being made transportable from machinery-mediated topsoil disturbance and the loss of vegetative cover and litter layers.

Local Climate Regulation

Beside the implications of large-scale logging for global warming, drastic changes in precipitation are direct and immediate when the forest cover is removed.174 Changes in transpiration result in a greater intensity of tropical rainfall, enhancing both run-off and erosion, even if the total amount of rainfall remains unchanged. Forest loss can also make rainfall more erratic, thus lengthening dry periods.175

Forest Fires

Most of the destructive forest fires that have recently raged out of control across the world, from the Amazon to Indonesia, are widely acknowledged to have been either started by and/or exacerbated by logging and agricultural development companies, such as the oil palm industry. One of the most detailed studies on the effects of fires in Kalimantan, Indonesia, concludes that the considerable decrease in foliage and related changes in the stand structure, increase of albedo, and horizontal and vertical air movements caused by fires, may produce significant and lasting effects on the regional climate.176

Impacts on the Marine Environment

Unsustainable logging mobilises debris that not only finds its way into the streams and rivers but also to the marine environment, where it damages mangroves and coral reefs, habitats crucial for aquatic life. In the Solomon Islands, the unique Marovo Lagoon, a proposed World Heritage Site, is threatened by the ecologically-destructive logging operations occurring in the surrounding forests. In Papua New Guinea, coral reefs have been destroyed to construct log ponds.

Loss of Biodiversity

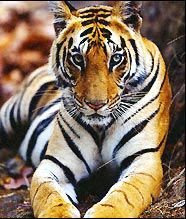

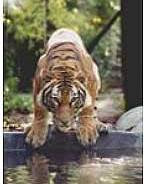

Logging often destroys natural habitats, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and sometimes leading to the local, and possibly global, extinction of species. Although estimates of the rates of loss vary, few deny the reality of the current losses of both flora and fauna.177

According to a joint report by the Worldwide Fund for Nature and the Sarawak Forest Department, "Logging causes immediate forest disturbances, long-term habitat changes (e.g. damage to food trees and salt-licks), increased hunting by timber company workers and availability of logging roads as hunting routes. The destruction of wildlife from habitat loss must be recognised to be on an enormous scale".178 In Central Africa, the opening-up of the forest by logging facilitates the illegal hunting of wildlife, including protected species such as primates, and is leading to a decline in wildlife populations.179 Deterioration in water quality has caused a decline in fish stocks and has affected aquatic biological diversity because indigenous animals and plant life are highly vulnerable to oxygen depletion, suspended particulate matter and a lack of light.180

Even so called selective logging severely affects the complex and rich biodiversity of forests through excessive damage to residual stands, destruction of other plant and tree species and the creaming-off of species which are the most valuable for timber. An FAO study in Malaysia has shown that as much as 50% of the standing forest may be damaged and the surface soil destroyed when up to 30% of the ground surface is exposed. During silvicultural treatment in logging operations in Sarawak, so-called uneconomic forest species are deliberately poisoned. This reduces the complexity and species diversity of the tropical forests to only 10% of the original condition, resulting in the systematic elimination of tree genetic resources and contamination of the environment.181 According to the IUCN the most frequently recorded of all threats to globally endangered tree species is 'felling'

Destructive logging practices using heavy machinery seriously reduce the forest's ability to carry out vital environmental and ecological functions.

Watershed Management and Soil Erosion

Forests provide a buffer to filter water and to hold soil in place. They sustain water and soil resources through recycling nutrients. In watersheds where forests are degraded or destroyed, minimum flows decrease during the dry season, leading to drought, while peak floods and soil erosion increase during

Tributary meets Melinau River, upper reaches of Baram river. Tributary water (left of picture), from preserved, non-logged and non-eroded watershed. Water from main river is cloudy with sediment from logging operations.

Flooding along the Baram River in Sarawak has increased significantly since logging began, the major floods occurring in 1979 and 1981.168 Massive floods, directly linked to excessive logging, have caused hundreds of deaths in the Philippines169 and Thailand.170

Much of the current logging carried out in Sarawak and other places is on steep lands dominated by surface materials that are highly susceptible to erosion when disturbed.171 Data collected by the Malaysian Department of Environment in 90 long-term sampling site locations within 21 river basins has detected incredibly high suspended sediment loads in most rivers and tributaries. This mainly originates from upstream soil erosion caused by the indiscriminate construction of logging roads and camps, skid trails and logging itself.172 Dr Saulei of the University of Papua New Guinea also blames the logging industry for 'accelerating erosion, weathering and humus decomposition, and leading to widespread formation of soils with low nutrient and absorptive capacities'

A skid track with severe erosion. More than a metre of topsoil has been lost and the bedrock exposed along many metres of this skid track on Isabel Island, Solomon Islands (see Kumpulan Emas, page 44).

The scale of inputs of mobilised sediment is clearly seen in this photograph where many tonnes of material are being made transportable from machinery-mediated topsoil disturbance and the loss of vegetative cover and litter layers.

Local Climate Regulation

Beside the implications of large-scale logging for global warming, drastic changes in precipitation are direct and immediate when the forest cover is removed.174 Changes in transpiration result in a greater intensity of tropical rainfall, enhancing both run-off and erosion, even if the total amount of rainfall remains unchanged. Forest loss can also make rainfall more erratic, thus lengthening dry periods.175

Forest Fires

Most of the destructive forest fires that have recently raged out of control across the world, from the Amazon to Indonesia, are widely acknowledged to have been either started by and/or exacerbated by logging and agricultural development companies, such as the oil palm industry. One of the most detailed studies on the effects of fires in Kalimantan, Indonesia, concludes that the considerable decrease in foliage and related changes in the stand structure, increase of albedo, and horizontal and vertical air movements caused by fires, may produce significant and lasting effects on the regional climate.176

Impacts on the Marine Environment

Unsustainable logging mobilises debris that not only finds its way into the streams and rivers but also to the marine environment, where it damages mangroves and coral reefs, habitats crucial for aquatic life. In the Solomon Islands, the unique Marovo Lagoon, a proposed World Heritage Site, is threatened by the ecologically-destructive logging operations occurring in the surrounding forests. In Papua New Guinea, coral reefs have been destroyed to construct log ponds.

Loss of Biodiversity

Logging often destroys natural habitats, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and sometimes leading to the local, and possibly global, extinction of species. Although estimates of the rates of loss vary, few deny the reality of the current losses of both flora and fauna.177

According to a joint report by the Worldwide Fund for Nature and the Sarawak Forest Department, "Logging causes immediate forest disturbances, long-term habitat changes (e.g. damage to food trees and salt-licks), increased hunting by timber company workers and availability of logging roads as hunting routes. The destruction of wildlife from habitat loss must be recognised to be on an enormous scale".178 In Central Africa, the opening-up of the forest by logging facilitates the illegal hunting of wildlife, including protected species such as primates, and is leading to a decline in wildlife populations.179 Deterioration in water quality has caused a decline in fish stocks and has affected aquatic biological diversity because indigenous animals and plant life are highly vulnerable to oxygen depletion, suspended particulate matter and a lack of light.180

Even so called selective logging severely affects the complex and rich biodiversity of forests through excessive damage to residual stands, destruction of other plant and tree species and the creaming-off of species which are the most valuable for timber. An FAO study in Malaysia has shown that as much as 50% of the standing forest may be damaged and the surface soil destroyed when up to 30% of the ground surface is exposed. During silvicultural treatment in logging operations in Sarawak, so-called uneconomic forest species are deliberately poisoned. This reduces the complexity and species diversity of the tropical forests to only 10% of the original condition, resulting in the systematic elimination of tree genetic resources and contamination of the environment.181 According to the IUCN the most frequently recorded of all threats to globally endangered tree species is 'felling'

Destructive logging practices using heavy machinery seriously reduce the forest's ability to carry out vital environmental and ecological functions.

28 April 2010

pulp and paper_the star

Paper consumption is set to increase

The Star, 19 January 2009

KUALA LUMPUR: Paper consumption is set to increase over the years, and the Government should make it more attractive for local industrialists to set up more paper mills here in collaboration with foreign investors.

“More than half of what is used now is imported,” Malaysia Paper Merchants’ Association (MaPMA) secretary Manmohan Singh Kwatra said at its 20th anniversary dinner last night which was graced by Deputy Finance Minister Datuk Kong Cho Ha.

“About 150,000 tonnes is produced locally at the Sabah Forest Industries (SFI) in Sipitang, Sabah, Malaysia’s first integrated pulp and paper mill.”

Malaysia consumes about 380,000 tonnes of printing and writing paper annually, of which about 230,000 tonnes are imported, including from Indonesia and Thailand.

“With attractive incentives, our mill partners from the neighbouring countries will be more attracted to add on to, or shift, their operations to Malaysia, while SFI will certainly consider expansion plans to meet the present shortfall and the annual growing demand,” Manmohan added.

SFI’s production, he said, was set to increase to 180,000 tonnes a year within the next two years.

Kong meanwhile said the Government would always hold a dialogue with the industry prior to formulating a policy or law.

He encouraged the setting up of more paper mills in the country given that demand for paper would continue to rise.

“I encourage paper merchants to come together and invest in the industry so that we do not have to depend so much on imported paper, as imports can affect pricing,” he added.

He said the fluctuating oil prices had affected all industries, including the paper industry, making budgeting and purchasing difficult.

The Star, 19 January 2009

KUALA LUMPUR: Paper consumption is set to increase over the years, and the Government should make it more attractive for local industrialists to set up more paper mills here in collaboration with foreign investors.

“More than half of what is used now is imported,” Malaysia Paper Merchants’ Association (MaPMA) secretary Manmohan Singh Kwatra said at its 20th anniversary dinner last night which was graced by Deputy Finance Minister Datuk Kong Cho Ha.

“About 150,000 tonnes is produced locally at the Sabah Forest Industries (SFI) in Sipitang, Sabah, Malaysia’s first integrated pulp and paper mill.”

Malaysia consumes about 380,000 tonnes of printing and writing paper annually, of which about 230,000 tonnes are imported, including from Indonesia and Thailand.

“With attractive incentives, our mill partners from the neighbouring countries will be more attracted to add on to, or shift, their operations to Malaysia, while SFI will certainly consider expansion plans to meet the present shortfall and the annual growing demand,” Manmohan added.

SFI’s production, he said, was set to increase to 180,000 tonnes a year within the next two years.

Kong meanwhile said the Government would always hold a dialogue with the industry prior to formulating a policy or law.

He encouraged the setting up of more paper mills in the country given that demand for paper would continue to rise.

“I encourage paper merchants to come together and invest in the industry so that we do not have to depend so much on imported paper, as imports can affect pricing,” he added.

He said the fluctuating oil prices had affected all industries, including the paper industry, making budgeting and purchasing difficult.

21 April 2010

bahaya khawarij_penulisan Ust Emran Ahmad

Mazhab Khawarij adalah merupakan mazhab Aqidah yang paling lama dan terawal muncul selepas Ahlul Sunnah Wal Jamaah. Bahkan kemunculan mazhab Khawarij adalah lebih dahulu daripada Syi’ah.

Kalimah Khawarij di dalam bahasa Arab : خوارج bermaksud “Mereka yang Keluar” dan hal ini daripada sudut Istilah merujuk kepada kefahaman golongan yang keluar daripada ketaatan kepada Khalifah Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu serta menolaknya.

Ajaran Khawarij ini sebenarnya telah muncul semenjak di zaman rasulullah lagi apabila mereka ini dikenali sebagai kaum pemberontak dan penentang yang menganggap hanya mereka sahaja yang benar sedangkan orang lain semuanya salah.

Hal ini berlaku berdasarkan riwayat Abu Said Al-Khudri radiallahuanhu yang menceritakan bahawa ada seorang lelaki yang berkata kepada rasulullah sewaktu baginda membahagikan barangan kepada para sahabat supaya baginda berlaku adil. Maka ditegur oleh baginda dengan berkata : “Celakalah kamu bukankah aku ini orang yang paling bertaqwa kepada Allah ?” Maka Khalid Al-Walid ingin membunuh lelaki itu tetapi ditahan oleh Rasulullah dan baginda kemudian mengatakan bahawa daripada keturunan lelaki ini akan lahir golongan yang akan membaca Al-Quran tetapi bacaan itu tidak pun melewati kerongkong mereka dan agama ini akan terlepas daripada diri mereka seperti terlepasnya anak panah dari busurnya.

Menurut Kitab-kitab Firaq (perpecahan umat) awal kemunculan Khawarij secara rasmi ialah semasa zaman Amirul Mukminin Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu sewaktu terjadinya Majlis Tahkim bersama dengan Muawiyah radiallahuanhu. Mereka berkumpul disuatu tempat yang disebut Harurah (sebuah kawasan di daerah Kufah) dan membantah perlaksanaan Majlis tersebut kerana menganggap ianya membelakangi Kitab Allah dan hukum Allah swt.

Namun hakikatnya itu bukanlah punca sebenar mereka keluar daripada pasukan Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu.

Mereka juga sebelum kemunculan secara rasmi telah bertanggungjawab kepada beberapa siri fitnah dan kejahatan seperti pembunuhan Khalifah Utsman bin Affan radiallahuanhu. Setelah Utsman dibunuh, mereka kemudian bersembunyi ke dalam pasukan dan penyokong Ali bin Abi Tolib untuk mengelakkan diri mereka daripada diburu dan dibunuh balas oleh Muawiyah radiallahuanhu yang memiliki hubungan kekeluargaan dengan Khalifah Utsman bin Affan.

Pembunuh Utsman adalah tidak diketahui kerana jumlahnya ramai dan apabila Ali bertanya kepada golongan Khawarij ini siapakah yang membunuh Utsman maka ribuan manusia daripada penyokong Khawarij ini mengaku telah membunuh Utsman lalu hal itu menyebabkan Khalifah Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu menangguhkan usaha untuk melakukan Qisos ke atas Utsman sehingga menyebabkan ketidak puasan hati di sisi Muawiyah dan juga ramai sahabat yang lain.

Akhirnya terjadilah perang siffin kerana perbezaan pendapat dan juga kerana masing-masing pasukan diapi-apikan oleh golongan munafiqin (seperti kaum Khawarij dan Abdullah bin Saba’ daripada Syiah). Kemudian masing-masing pihak mengirim utusan untuk berunding maka terjadilah perdamaian antara kedua belah pihak dan Majlis Tahkim.

Melihat hal ini orang-orang Khawarij menjadi bimbang bahawa dengan perdamaian di antara Ali dan para sahabat seperti Muawiyah akan menyebabkan mereka ditangkap dan diburu kerana telah membunuh Utsman bin Affan radiallahuanhu maka akhirnya mereka pun melarikan diri dan keluar daripada pasukan Ali bin Abi Tolib dan menubuhkan pasukan mereka sendiri untuk menyelamatkan diri.

Mereka juga kemudian membuat perancangan untuk membunuh para pemimpin Islam seperti Khalifah Ali bin Abi Tolib dan Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan dan lain-lain sahabat radiallahuanhum tetapi hanya Ali yang berjaya di bunuh sewaktu solat subuh di masjid.

Khawarij menafsirkan Kitab Al-Quran secara zahir.

Mereka menolak tafsiran Al-Quran oleh para sahabat dan memahami Islam secara hukum zahir dan mengambil lafaz-lafaz Al-Quran secara zahir ayat. Hal ini menyebabkan mereka tersesat dan ditambah pula oleh sikap ta’asub mereka kepada diri mereka dan ibadah mereka yang tersangat banyak melebihi ibadah para sahabat menyebabkan mereka memperendahkan para sahabat rasulullah dan tidak mengambil hadis yang bertentangan dengan kefahaman dan tafsiran mereka.

Golongan Khawarij kemudian berkumpul serta berpusat di Nahrawan dan melantik Imam dan ketua perang mereka sendiri serta menubuhkan pasukan ketenteraan dan jamaah mereka dengan memiliki Imam solat, tukang azan dan mendirikan insititusi agama yang diharapkan dapat mengatasi ajaran Islam yang dikuasai oleh para sahabat rasulullah salallahualaihiwasalam.

Mereka mengkafirkan sejumlah besar para sahabat, khalifah-khalifah Islam dan umat Islam yang melakukan dosa besar serta maksiat pada pandangan mereka. Iman di sisi mereka ialah tetap dan tidak boleh berkurang dan jika berkurang pada seseorang kerana maksiat maka orang itu di sisi mereka telah menjadi kafir. Dakyah mereka sangat merbahaya sehingga mengakibatkan ramai para sahabat telah ditangkap dan dibunuh kerana pada anggapan mereka para sahabat rasulullah telah menjadi murtad disebabkan mereka tidak sefahaman dengan kepercayaan Khawarij.

Pokok seruan Khawarij ialah seperti berikut :

1) Kaum muslimin yang melakukan dosa besar adalah kafir

2) Al-Quran ditafsirkan menurut lafaz zahir

3) As-Sunnah tidak diterima sebagai hujah kerana nabi boleh tersalah dan tersilap dan para sahabat baginda tiada kelebihan bahkan kaum yang sesat

4) Pemimpin atau Imam boleh diangkat daripada sesiapa sahaja tidak semestinya daripada kaum Quraisy sebaliknya boleh jadi daripada hamba dan bahkan daripada kaum wanita.

5) Para sahabat yang terlibat di dalam perang Jamal, menerima majlis Tahkim ialah kafir.

Tokoh-tokoh utama Khawarij ialah Abdullah bin Wahhab ar-Rasyidi , Urwah bin Hudair , Mustarid bin Sa'ad , Hausarah al-Asadi , Quraib bin Maruah , Nafi' bin al-Azraq , Abdullah bin Basyir , Najdah bin Amir al-Hanafi yang mana setiap daripada mereka ini kemudian mempunyai pengikut dan menghasilkan cabang daripada ajaran Khawarij yang tambah menyesatkan dan menyeleweng daripada Islam yang lurus.

Sehingga kini sebilangan kecil Mazhab Kahwarij masih wujud di dunia Islam seperti kelompok Ibadi di Negara Oman, Zanzibar, dan Maghrib walaubagaimanapun mereka menolak untuk dikenali sebagai Khawarij.

Kesimpulannya Imam Al-Shahrastani menyatakan bahawa sesiapa yang keluar memberontak daripada Imam yang sah dilantik oleh jamaah umat Islam ialah Khawarij tidak kira apakah di zaman sahabat, tabien atau selepas mereka selama wujud Imam-imam yang sah. (Lihat : Kitab Al-Milal Wa Al-Nihal, Jilid 1, ms. 101)

Golongan salaf pula menjelaskan bahawa Khawarij ini ialah golongan yang beramal di dalam Islam menurut pendapat mereka sendiri dan mengambil ayat-ayat zahir di dalam Al-Quran tanpa merujuk kefahaman salaf soleh dan penafsiran rasulullah serta menolak hadis rasulullah dan tafsiran agama oleh para sahabat baginda.

Semoga Allah menjauhkan kita daripada mereka.

http://ustaz.blogspot.com/

Kalimah Khawarij di dalam bahasa Arab : خوارج bermaksud “Mereka yang Keluar” dan hal ini daripada sudut Istilah merujuk kepada kefahaman golongan yang keluar daripada ketaatan kepada Khalifah Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu serta menolaknya.

Ajaran Khawarij ini sebenarnya telah muncul semenjak di zaman rasulullah lagi apabila mereka ini dikenali sebagai kaum pemberontak dan penentang yang menganggap hanya mereka sahaja yang benar sedangkan orang lain semuanya salah.

Hal ini berlaku berdasarkan riwayat Abu Said Al-Khudri radiallahuanhu yang menceritakan bahawa ada seorang lelaki yang berkata kepada rasulullah sewaktu baginda membahagikan barangan kepada para sahabat supaya baginda berlaku adil. Maka ditegur oleh baginda dengan berkata : “Celakalah kamu bukankah aku ini orang yang paling bertaqwa kepada Allah ?” Maka Khalid Al-Walid ingin membunuh lelaki itu tetapi ditahan oleh Rasulullah dan baginda kemudian mengatakan bahawa daripada keturunan lelaki ini akan lahir golongan yang akan membaca Al-Quran tetapi bacaan itu tidak pun melewati kerongkong mereka dan agama ini akan terlepas daripada diri mereka seperti terlepasnya anak panah dari busurnya.

Menurut Kitab-kitab Firaq (perpecahan umat) awal kemunculan Khawarij secara rasmi ialah semasa zaman Amirul Mukminin Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu sewaktu terjadinya Majlis Tahkim bersama dengan Muawiyah radiallahuanhu. Mereka berkumpul disuatu tempat yang disebut Harurah (sebuah kawasan di daerah Kufah) dan membantah perlaksanaan Majlis tersebut kerana menganggap ianya membelakangi Kitab Allah dan hukum Allah swt.

Namun hakikatnya itu bukanlah punca sebenar mereka keluar daripada pasukan Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu.

Mereka juga sebelum kemunculan secara rasmi telah bertanggungjawab kepada beberapa siri fitnah dan kejahatan seperti pembunuhan Khalifah Utsman bin Affan radiallahuanhu. Setelah Utsman dibunuh, mereka kemudian bersembunyi ke dalam pasukan dan penyokong Ali bin Abi Tolib untuk mengelakkan diri mereka daripada diburu dan dibunuh balas oleh Muawiyah radiallahuanhu yang memiliki hubungan kekeluargaan dengan Khalifah Utsman bin Affan.

Pembunuh Utsman adalah tidak diketahui kerana jumlahnya ramai dan apabila Ali bertanya kepada golongan Khawarij ini siapakah yang membunuh Utsman maka ribuan manusia daripada penyokong Khawarij ini mengaku telah membunuh Utsman lalu hal itu menyebabkan Khalifah Ali bin Abi Tolib radiallahuanhu menangguhkan usaha untuk melakukan Qisos ke atas Utsman sehingga menyebabkan ketidak puasan hati di sisi Muawiyah dan juga ramai sahabat yang lain.

Akhirnya terjadilah perang siffin kerana perbezaan pendapat dan juga kerana masing-masing pasukan diapi-apikan oleh golongan munafiqin (seperti kaum Khawarij dan Abdullah bin Saba’ daripada Syiah). Kemudian masing-masing pihak mengirim utusan untuk berunding maka terjadilah perdamaian antara kedua belah pihak dan Majlis Tahkim.

Melihat hal ini orang-orang Khawarij menjadi bimbang bahawa dengan perdamaian di antara Ali dan para sahabat seperti Muawiyah akan menyebabkan mereka ditangkap dan diburu kerana telah membunuh Utsman bin Affan radiallahuanhu maka akhirnya mereka pun melarikan diri dan keluar daripada pasukan Ali bin Abi Tolib dan menubuhkan pasukan mereka sendiri untuk menyelamatkan diri.

Mereka juga kemudian membuat perancangan untuk membunuh para pemimpin Islam seperti Khalifah Ali bin Abi Tolib dan Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan dan lain-lain sahabat radiallahuanhum tetapi hanya Ali yang berjaya di bunuh sewaktu solat subuh di masjid.

Khawarij menafsirkan Kitab Al-Quran secara zahir.

Mereka menolak tafsiran Al-Quran oleh para sahabat dan memahami Islam secara hukum zahir dan mengambil lafaz-lafaz Al-Quran secara zahir ayat. Hal ini menyebabkan mereka tersesat dan ditambah pula oleh sikap ta’asub mereka kepada diri mereka dan ibadah mereka yang tersangat banyak melebihi ibadah para sahabat menyebabkan mereka memperendahkan para sahabat rasulullah dan tidak mengambil hadis yang bertentangan dengan kefahaman dan tafsiran mereka.

Golongan Khawarij kemudian berkumpul serta berpusat di Nahrawan dan melantik Imam dan ketua perang mereka sendiri serta menubuhkan pasukan ketenteraan dan jamaah mereka dengan memiliki Imam solat, tukang azan dan mendirikan insititusi agama yang diharapkan dapat mengatasi ajaran Islam yang dikuasai oleh para sahabat rasulullah salallahualaihiwasalam.

Mereka mengkafirkan sejumlah besar para sahabat, khalifah-khalifah Islam dan umat Islam yang melakukan dosa besar serta maksiat pada pandangan mereka. Iman di sisi mereka ialah tetap dan tidak boleh berkurang dan jika berkurang pada seseorang kerana maksiat maka orang itu di sisi mereka telah menjadi kafir. Dakyah mereka sangat merbahaya sehingga mengakibatkan ramai para sahabat telah ditangkap dan dibunuh kerana pada anggapan mereka para sahabat rasulullah telah menjadi murtad disebabkan mereka tidak sefahaman dengan kepercayaan Khawarij.

Pokok seruan Khawarij ialah seperti berikut :

1) Kaum muslimin yang melakukan dosa besar adalah kafir

2) Al-Quran ditafsirkan menurut lafaz zahir

3) As-Sunnah tidak diterima sebagai hujah kerana nabi boleh tersalah dan tersilap dan para sahabat baginda tiada kelebihan bahkan kaum yang sesat

4) Pemimpin atau Imam boleh diangkat daripada sesiapa sahaja tidak semestinya daripada kaum Quraisy sebaliknya boleh jadi daripada hamba dan bahkan daripada kaum wanita.

5) Para sahabat yang terlibat di dalam perang Jamal, menerima majlis Tahkim ialah kafir.

Tokoh-tokoh utama Khawarij ialah Abdullah bin Wahhab ar-Rasyidi , Urwah bin Hudair , Mustarid bin Sa'ad , Hausarah al-Asadi , Quraib bin Maruah , Nafi' bin al-Azraq , Abdullah bin Basyir , Najdah bin Amir al-Hanafi yang mana setiap daripada mereka ini kemudian mempunyai pengikut dan menghasilkan cabang daripada ajaran Khawarij yang tambah menyesatkan dan menyeleweng daripada Islam yang lurus.

Sehingga kini sebilangan kecil Mazhab Kahwarij masih wujud di dunia Islam seperti kelompok Ibadi di Negara Oman, Zanzibar, dan Maghrib walaubagaimanapun mereka menolak untuk dikenali sebagai Khawarij.

Kesimpulannya Imam Al-Shahrastani menyatakan bahawa sesiapa yang keluar memberontak daripada Imam yang sah dilantik oleh jamaah umat Islam ialah Khawarij tidak kira apakah di zaman sahabat, tabien atau selepas mereka selama wujud Imam-imam yang sah. (Lihat : Kitab Al-Milal Wa Al-Nihal, Jilid 1, ms. 101)

Golongan salaf pula menjelaskan bahawa Khawarij ini ialah golongan yang beramal di dalam Islam menurut pendapat mereka sendiri dan mengambil ayat-ayat zahir di dalam Al-Quran tanpa merujuk kefahaman salaf soleh dan penafsiran rasulullah serta menolak hadis rasulullah dan tafsiran agama oleh para sahabat baginda.

Semoga Allah menjauhkan kita daripada mereka.

http://ustaz.blogspot.com/

perisai untuk anak_penulisan ustaz Emran Ahmad

Berikut ialah nasihat dan pedoman untuk memagari rumah dan anak-anak daripada gangguan syaitan seperti yang diajarkan oleh Al-Quran dan As-sunnah.

1. Membaca surah Al-baqarah di dalam rumah

Rasullullah bersabda:"Janganlah jadikan rumah kamu sebagai kuburan. Sesungguhnya rumah yang dibacakan padanya surah Al-Baqarah tidak akan dimasuki syaitan." (Hadis riwayat Muslim)

2. Membaca Bismillah sebelum masuk dan semasa keluar daripada rumah

3. Membaca ayat kursi kepada anak-anak sebelum tidur

{ اللَّهُ لا إِلَهَ إِلاَّ هُوَ الْحَيُّ الْقَيُّومُ لا تَأْخُذُهُ سِنَةٌ وَلا نَوْمٌ لَهُ مَا فِي السَّمَوَاتِ وَمَا فِي الأَرْضِ مَنْ ذَا الَّذِي يَشْفَعُ عِنْدَهُ إِلاَّ بِإِذْنِهِ يَعْلَمُ مَا بَيْنَ أَيْدِيهِمْ وَمَا خَلْفَهُمْ وَلا يُحِيطُونَ بِشَيْءٍ مِنْ عِلْمِهِ إِلاَّ بِمَا شَاءَ وَسِعَ كُرْسِيُّهُ السَّمَوَاتِ وَالأَرْضَ وَلا يَئُودُهُ حِفْظُهُمَا وَهُوَ الْعَلِيُّ الْعَظِيمُ }

4. Membaca doa berikut kepada anak, sambil tangan mengusap kepalanya :

اعذك بكلمات الله التامة من كل شيطان وشره

Maksudnya : “Aku mohon perlindungan untuk kamu dengan kalimah-kalimah Allah yang sempurna dan semua perbuatan syaitan dan kejahatannya.”

5. Membaca Surah Al-Ikhlas, Al-Falaq dan An-Nas kemudian sapu seluruh badan sebelum tidur

Satu hadith daripada Aishah RA, mengatakan, bahawa apabila Rasulullah صلى الله عليه وسلم berbaring di perbaringan baginda pada malam hari, baginda menyatukan kedua telapak tangan baginda lalu baginda meniup keduanya dan membacakan surah Al-Ikhlas, Al-Falaq dan An-Nas. Kemudian baginda mengusap tubuh baginda yang mampu diusap dengan kedua tangannya. Baginda mulai dari kepala, wajah, dan bahagian muka tubuhnya. Baginda melakukan hal itu tiga kali.“ (Hadith sahih Bukhari, riwayat Aishah RA)

6. Bersihkan hidung jika terjaga tengah malam

Abu Hurairah RA berkata, bahawa Rasulullah صلى الله عليه وسلم bersabda, maksudnya: “Apabila salah seorang di antara kamu terbangun dari mimpinya, hendaklah dia melakukan membersihkan hidungnya tiga kali, kerana syaitan bermalam pada hidungnya.” (Hadith Riwayat Bukhari dan Muslim)

7. Disebut dalam Sahih Muslim, diriwayatkan daripada Abu Hurairah r.a katanya: Rasulullah صلى الله عليه وسلم bersabda (maksudnya): Sesiapa yang membaca 100 kali :

لا إله إلا الله وحده لا شريك له له الملك وله الحمد وهو على كل شيء قدير

dibuat untuknya benteng sebagai pelindung dari syaitan pada hari tersebut hingga ke petang.

p/s :

Demi menjadikan amalan di atas berkesan maka terlebih dahulu orang yang mengamalkannya haruslah beriman dan melaksanakan perintah Al-Quran itu sendiri serta membersihkan diri dan ahli keluarganya daripada syirik dan maksiat kepada Allah SWT kerana tiadalah makbul doa melainkan dari jiwa yang suci daripada syirik dan derhaka kepada Allah SWT.

http://ustaz.blogspot.com/

1. Membaca surah Al-baqarah di dalam rumah

Rasullullah bersabda:"Janganlah jadikan rumah kamu sebagai kuburan. Sesungguhnya rumah yang dibacakan padanya surah Al-Baqarah tidak akan dimasuki syaitan." (Hadis riwayat Muslim)

2. Membaca Bismillah sebelum masuk dan semasa keluar daripada rumah

3. Membaca ayat kursi kepada anak-anak sebelum tidur

{ اللَّهُ لا إِلَهَ إِلاَّ هُوَ الْحَيُّ الْقَيُّومُ لا تَأْخُذُهُ سِنَةٌ وَلا نَوْمٌ لَهُ مَا فِي السَّمَوَاتِ وَمَا فِي الأَرْضِ مَنْ ذَا الَّذِي يَشْفَعُ عِنْدَهُ إِلاَّ بِإِذْنِهِ يَعْلَمُ مَا بَيْنَ أَيْدِيهِمْ وَمَا خَلْفَهُمْ وَلا يُحِيطُونَ بِشَيْءٍ مِنْ عِلْمِهِ إِلاَّ بِمَا شَاءَ وَسِعَ كُرْسِيُّهُ السَّمَوَاتِ وَالأَرْضَ وَلا يَئُودُهُ حِفْظُهُمَا وَهُوَ الْعَلِيُّ الْعَظِيمُ }

4. Membaca doa berikut kepada anak, sambil tangan mengusap kepalanya :

اعذك بكلمات الله التامة من كل شيطان وشره

Maksudnya : “Aku mohon perlindungan untuk kamu dengan kalimah-kalimah Allah yang sempurna dan semua perbuatan syaitan dan kejahatannya.”

5. Membaca Surah Al-Ikhlas, Al-Falaq dan An-Nas kemudian sapu seluruh badan sebelum tidur

Satu hadith daripada Aishah RA, mengatakan, bahawa apabila Rasulullah صلى الله عليه وسلم berbaring di perbaringan baginda pada malam hari, baginda menyatukan kedua telapak tangan baginda lalu baginda meniup keduanya dan membacakan surah Al-Ikhlas, Al-Falaq dan An-Nas. Kemudian baginda mengusap tubuh baginda yang mampu diusap dengan kedua tangannya. Baginda mulai dari kepala, wajah, dan bahagian muka tubuhnya. Baginda melakukan hal itu tiga kali.“ (Hadith sahih Bukhari, riwayat Aishah RA)

6. Bersihkan hidung jika terjaga tengah malam

Abu Hurairah RA berkata, bahawa Rasulullah صلى الله عليه وسلم bersabda, maksudnya: “Apabila salah seorang di antara kamu terbangun dari mimpinya, hendaklah dia melakukan membersihkan hidungnya tiga kali, kerana syaitan bermalam pada hidungnya.” (Hadith Riwayat Bukhari dan Muslim)

7. Disebut dalam Sahih Muslim, diriwayatkan daripada Abu Hurairah r.a katanya: Rasulullah صلى الله عليه وسلم bersabda (maksudnya): Sesiapa yang membaca 100 kali :

لا إله إلا الله وحده لا شريك له له الملك وله الحمد وهو على كل شيء قدير

dibuat untuknya benteng sebagai pelindung dari syaitan pada hari tersebut hingga ke petang.

p/s :

Demi menjadikan amalan di atas berkesan maka terlebih dahulu orang yang mengamalkannya haruslah beriman dan melaksanakan perintah Al-Quran itu sendiri serta membersihkan diri dan ahli keluarganya daripada syirik dan maksiat kepada Allah SWT kerana tiadalah makbul doa melainkan dari jiwa yang suci daripada syirik dan derhaka kepada Allah SWT.

http://ustaz.blogspot.com/

20 April 2010

18 April 2010

17 April 2010

15 April 2010

14 April 2010

forest protection and management

Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories

Basic Concepts

The starting point must be a definition of a protected area. The definition adopted is derived from that of the workshop on Categories held at the IVth World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas:

An area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means.

This definition embraces the 'universe' of protected areas. All categories must fall within this definition. But although all protected areas meet the general purposes contained in this definition, in practice the precise purposes for which protected areas are managed differ greatly. The following are the main purposes of management:

Scientific research

Wilderness protection

Preservation of species and genetic diversity

Maintenance of environmental services

Protection of specific natural and cultural features

Tourism and recreation

Education

Sustainable use of resources from natural ecosystems

Maintenance of cultural and traditional attributes

Having regard to the different mix and priorities accorded to these main management objectives, the following emerge clearly as distinct categories of protected areas:

Areas managed mainly for:

I Strict protection (i.e. Strict Nature Reserve / Wilderness Area)

II Ecosystem conservation and recreation (i.e. National Park)

III Conservation of natural features (i.e. Natural Monument)

IV Conservation through active management (i.e. Habitat/Species Management Area)

V Landscape/seascape conservation and recreation (i.e. Protected Landscape/Seascape)

VI Sustainable use of natural ecosystems (i.e. Managed Resource Protected Area)

However, most protected areas also serve a range of secondary management objectives.

The relationship between management objectives and the categories is illustrated in matrix form in the table below. It is developed further in Part II, where each category is described, and through a range of examples presented in Part III.

This analysis is the foundation upon which the international system for categorising protected areas was developed by IUCN and which is presented in these guidelines. There are several important features to note:

the basis of categorisation is by primary management objective;

assignment to a category is not a commentary on management effectiveness;

the categories system is international;

Table Matrix of management objectives and IUCN protected area management categories

MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVE

Ia

Ib

II

III

IV

V

VI

Scientific research

1

3

2

2

2

2

3

Wilderness protection

2

1

2

3

3

-

2

Preservation of species and genetic diversity

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

Maintenance of environmental services

2

1

1

-

1

2

1

Protection of specific natural/cultural features

-

-

2

1

3

1

3

Tourism and recreation

-

2

1

1

3

1

3

Education

-

-

2

2

2

2

3

Sustainable use of resources from natural ecosystems

-

3

3

-

2

2

1

Maintenance of cultural/traditional attributes

-

-

-

-

-

1

2

Key:

1 Primary objective

2 Secondary objective

3 Potentially applicable objective

- Not applicable

national names for protected areas may vary;

a new category is introduced;

all categories are important;

but they imply a gradation of human intervention.

These points are discussed in turn.

The Basis of Categorisation is by Primary Management Objective

In the first instance, categories should be assigned on the basis of the primary management objective as contained in the legal definitions on which it was established; site management objectives are of supplementary value. This approach ensures a solid basis to the system, and is more practical. In assigning an area to a category, therefore, national legislation (or similar effective means, such as customary agreements or the declared objectives of a non-governmental organization) will need to be examined to identify the primary objective for which the area is to be managed.

Assignment to a Category is not a Commentary on Management Effectiveness

In interpreting the 1978 system, some have tended to confuse management effectiveness with management objectives. For example, some areas which were set up under law with objectives appropriate to Category II National Parks have been reassigned to Category V Protected Landscapes because they have not been protected effectively against human encroachment. This is to confuse two separate judgements: what an area is intended to be; and how it is run. IUCN is developing a separate system for monitoring and recording management effectiveness; when complete, this will be promoted alongside the categories system, and information on management effectiveness will also be collected and recorded at the international level.

The Categories System is International

The system of categories has been developed, inter alia, to provide a basis for international comparison. Moreover, it is intended for use in all countries. Therefore the guidance is inevitably fairly general and will need to be interpreted with flexibility at national and regional levels. It also follows from the international nature of the system, and from the need for consistent application of the categories, that the final responsibility for determining categories should be taken at the international level. This could be IUCN, as advised by its CNPPA and/or the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (e.g., in the compilation of the UN List) in close collaboration with IUCN.

National Names for Protected Areas may Vary

In a perfect world, IUCN's system of categories would have been in place first, and national systems would have followed on, using standard terminology. In practice, of course, different countries have set up national systems using widely varying terminology. To take one example, 'national parks' mean quite different things in different countries. Many nationally-designated 'national parks' do not strictly meet the criteria set by Category II under the 1978 system. In the United Kingdom, for example, 'National Parks' contain human settlement and extensive resource use, and are properly assigned to Category V. In South America, a recent IUCN study found that some 84 percent of national parks have significant resident human populations; some of these might be more appropriately placed in another category.

Since so much confusion has been caused by this in the past, Part II of these guidelines identifies the categories by their main objectives of management as well as their specific titles. Reference is also made to the titles used in the 1978 system because some, at least, have become widely known.

At the national level, of course, a variety of titles will continue to be used. Because of this, it is inevitable that the same title may mean different things in different countries; and different titles in different countries may be used to describe the same category of protected area. This is all the more reason for emphasising an international system of categorisation identified by management objectives in a system which does not depend on titles.

A New Category is Introduced

The Recommendation adopted at Caracas invited IUCN to consider further the views of some experts that a category is needed to cover predominantly natural areas which "are managed to protect their biodiversity in such a way as to provide a sustainable flow of products and services for the community". Consideration of this request has led to the inclusion in these guidelines of a category where the principal purpose of management is the sustainable use of natural ecosystems. The key point is that the area must be managed so that the long-term protection and maintenance of its biodiversity is assured. In particular, four considerations must be met:

the area must be able to fit within the overall definition of a protected area (see above),

at least two-thirds of the area should be, and is planned to remain in its natural state,

large commercial plantations are not to be included, and

a management authority must be in place.

Only if all these requirements are satisfied, can areas qualify for inclusion in this category.

All Categories are Important

The number assigned to a category does not reflect its importance: all categories are needed for conservation and sustainable development. Therefore IUCN encourages countries to develop a system of protected areas that meets its own natural and cultural heritage objectives and then apply any or all the appropriate categories. Since each category fills a particular 'niche' in management terms, all countries should consider the appropriateness of the full range of management categories to their needs.

...But they imply a Gradation of Human Intervention

However, it is inherent in the system that the categories represent varying degrees of human intervention. It is true that research has shown that the extent of past human modification of ecosystems has in fact been more pervasive than was previously supposed; and that no part of the globe can escape the effects of long-distance pollution and human-induced climate change. In that sense, no area on earth can be regarded as truly 'natural'. The term is therefore used here as it is defined in Caring for the Earth:

Ecosystems where since the industrial revolution (1750) human impact (a) has been no greater than that of any other native species, and (b) has not affected the ecosystem's structure. Climate change is excluded from this definition.

Under this definition, categories I to III are mainly concerned with the protection of natural areas where direct human intervention and modification of the environment has been limited; in categories IV, V and VI significantly greater intervention and modification will be found.

Basic Concepts

The starting point must be a definition of a protected area. The definition adopted is derived from that of the workshop on Categories held at the IVth World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas:

An area of land and/or sea especially dedicated to the protection and maintenance of biological diversity, and of natural and associated cultural resources, and managed through legal or other effective means.

This definition embraces the 'universe' of protected areas. All categories must fall within this definition. But although all protected areas meet the general purposes contained in this definition, in practice the precise purposes for which protected areas are managed differ greatly. The following are the main purposes of management:

Scientific research

Wilderness protection

Preservation of species and genetic diversity

Maintenance of environmental services

Protection of specific natural and cultural features

Tourism and recreation

Education

Sustainable use of resources from natural ecosystems

Maintenance of cultural and traditional attributes

Having regard to the different mix and priorities accorded to these main management objectives, the following emerge clearly as distinct categories of protected areas:

Areas managed mainly for:

I Strict protection (i.e. Strict Nature Reserve / Wilderness Area)

II Ecosystem conservation and recreation (i.e. National Park)

III Conservation of natural features (i.e. Natural Monument)

IV Conservation through active management (i.e. Habitat/Species Management Area)

V Landscape/seascape conservation and recreation (i.e. Protected Landscape/Seascape)

VI Sustainable use of natural ecosystems (i.e. Managed Resource Protected Area)

However, most protected areas also serve a range of secondary management objectives.

The relationship between management objectives and the categories is illustrated in matrix form in the table below. It is developed further in Part II, where each category is described, and through a range of examples presented in Part III.

This analysis is the foundation upon which the international system for categorising protected areas was developed by IUCN and which is presented in these guidelines. There are several important features to note:

the basis of categorisation is by primary management objective;

assignment to a category is not a commentary on management effectiveness;

the categories system is international;

Table Matrix of management objectives and IUCN protected area management categories

MANAGEMENT OBJECTIVE

Ia

Ib

II

III

IV

V

VI

Scientific research

1

3

2

2

2

2

3

Wilderness protection

2

1

2

3

3

-

2

Preservation of species and genetic diversity

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

Maintenance of environmental services

2

1

1

-

1

2

1

Protection of specific natural/cultural features

-

-

2

1

3

1

3

Tourism and recreation

-

2

1

1

3

1

3

Education

-

-

2

2

2

2

3

Sustainable use of resources from natural ecosystems

-

3

3

-

2

2

1

Maintenance of cultural/traditional attributes

-

-

-

-

-

1

2

Key:

1 Primary objective

2 Secondary objective

3 Potentially applicable objective

- Not applicable

national names for protected areas may vary;

a new category is introduced;

all categories are important;

but they imply a gradation of human intervention.

These points are discussed in turn.

The Basis of Categorisation is by Primary Management Objective

In the first instance, categories should be assigned on the basis of the primary management objective as contained in the legal definitions on which it was established; site management objectives are of supplementary value. This approach ensures a solid basis to the system, and is more practical. In assigning an area to a category, therefore, national legislation (or similar effective means, such as customary agreements or the declared objectives of a non-governmental organization) will need to be examined to identify the primary objective for which the area is to be managed.

Assignment to a Category is not a Commentary on Management Effectiveness

In interpreting the 1978 system, some have tended to confuse management effectiveness with management objectives. For example, some areas which were set up under law with objectives appropriate to Category II National Parks have been reassigned to Category V Protected Landscapes because they have not been protected effectively against human encroachment. This is to confuse two separate judgements: what an area is intended to be; and how it is run. IUCN is developing a separate system for monitoring and recording management effectiveness; when complete, this will be promoted alongside the categories system, and information on management effectiveness will also be collected and recorded at the international level.

The Categories System is International

The system of categories has been developed, inter alia, to provide a basis for international comparison. Moreover, it is intended for use in all countries. Therefore the guidance is inevitably fairly general and will need to be interpreted with flexibility at national and regional levels. It also follows from the international nature of the system, and from the need for consistent application of the categories, that the final responsibility for determining categories should be taken at the international level. This could be IUCN, as advised by its CNPPA and/or the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (e.g., in the compilation of the UN List) in close collaboration with IUCN.

National Names for Protected Areas may Vary

In a perfect world, IUCN's system of categories would have been in place first, and national systems would have followed on, using standard terminology. In practice, of course, different countries have set up national systems using widely varying terminology. To take one example, 'national parks' mean quite different things in different countries. Many nationally-designated 'national parks' do not strictly meet the criteria set by Category II under the 1978 system. In the United Kingdom, for example, 'National Parks' contain human settlement and extensive resource use, and are properly assigned to Category V. In South America, a recent IUCN study found that some 84 percent of national parks have significant resident human populations; some of these might be more appropriately placed in another category.

Since so much confusion has been caused by this in the past, Part II of these guidelines identifies the categories by their main objectives of management as well as their specific titles. Reference is also made to the titles used in the 1978 system because some, at least, have become widely known.

At the national level, of course, a variety of titles will continue to be used. Because of this, it is inevitable that the same title may mean different things in different countries; and different titles in different countries may be used to describe the same category of protected area. This is all the more reason for emphasising an international system of categorisation identified by management objectives in a system which does not depend on titles.

A New Category is Introduced

The Recommendation adopted at Caracas invited IUCN to consider further the views of some experts that a category is needed to cover predominantly natural areas which "are managed to protect their biodiversity in such a way as to provide a sustainable flow of products and services for the community". Consideration of this request has led to the inclusion in these guidelines of a category where the principal purpose of management is the sustainable use of natural ecosystems. The key point is that the area must be managed so that the long-term protection and maintenance of its biodiversity is assured. In particular, four considerations must be met:

the area must be able to fit within the overall definition of a protected area (see above),

at least two-thirds of the area should be, and is planned to remain in its natural state,

large commercial plantations are not to be included, and

a management authority must be in place.

Only if all these requirements are satisfied, can areas qualify for inclusion in this category.

All Categories are Important

The number assigned to a category does not reflect its importance: all categories are needed for conservation and sustainable development. Therefore IUCN encourages countries to develop a system of protected areas that meets its own natural and cultural heritage objectives and then apply any or all the appropriate categories. Since each category fills a particular 'niche' in management terms, all countries should consider the appropriateness of the full range of management categories to their needs.

...But they imply a Gradation of Human Intervention

However, it is inherent in the system that the categories represent varying degrees of human intervention. It is true that research has shown that the extent of past human modification of ecosystems has in fact been more pervasive than was previously supposed; and that no part of the globe can escape the effects of long-distance pollution and human-induced climate change. In that sense, no area on earth can be regarded as truly 'natural'. The term is therefore used here as it is defined in Caring for the Earth:

Ecosystems where since the industrial revolution (1750) human impact (a) has been no greater than that of any other native species, and (b) has not affected the ecosystem's structure. Climate change is excluded from this definition.

Under this definition, categories I to III are mainly concerned with the protection of natural areas where direct human intervention and modification of the environment has been limited; in categories IV, V and VI significantly greater intervention and modification will be found.

protected area management

INTRODUCTION

At the IV World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, meeting in Caracas, Venezuela in February 1992, participants concluded that more and better managed protected areas were urgently required. Participants emphasised that protected areas are about meeting people's needs: that protected areas should not be islands in a sea of development but must be part of every country's strategy for sustainable management and the wise use of its natural resources, and must be set in a regional planning context.

The Caracas Congress also declared its belief in the importance of the full range of protected areas, from those that protect the world's great natural areas to those that contain modified landscapes of outstanding scenic and cultural importance. Within this broad spectrum of uses, many names have been applied to protected areas; Australia alone uses some 45 names and the US National Park Service has 18 different types of areas under its mandate. Globally, over 140 names have been applied to protected areas of various types. Bringing some order to this diversity is clearly a very useful step.

The purpose of these guidelines, therefore, is to establish greater understanding among all concerned about the different categories of protected areas. A central principle upon which the guidelines are based is that categories should be defined by the objectives of management, not by the title of the area nor by the effectiveness of management in meeting those objectives. The matter of management effectiveness certainly needs to be addressed, but it is not seen as an issue of categorisation.

The guidelines build on work done by IUCN in this field over the past of a quarter century. In particular, they draw on the efforts of a task force established in 1984. They reflect the outcome of a wide-ranging debate over the past few years among protected area managers from around the world, including discussion and review at a workshop in Caracas. The outcome of this workshop was that the Congress adopted a recommendation urging that the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas and the IUCN Council endorse a system of categories for protected areas according to management objectives and that the system be commended to governments and explained through guidelines. The present publication is designed to give effect to this particular recommendation.

It is hoped that these guidelines will be used widely by those planning to set up new protected areas, and by those reviewing existing ones. They are designed to form a useful basis for preparing national protected areas systems plans. It is to be emphasized that these categories must in no way be considered as a 'driving' mechanism for governments or organizations in deciding the purposes of potential protected areas. Protected areas should be established to meet objectives consistent with national, local or private goals and needs (or a mixture of these) and only then be labelled with an IUCN category according to the management objectives developed herein. These categories have been developed to facilitate communication and information, not to drive the system.

The guidelines do not stand alone, of course. Much other advice on the management of protected areas has been published by IUCN in recent years, and more is to come as the fruits of the work at Caracas emerge in print. But these guidelines have a special significance as they are intended for everyone professionally involved in protected areas, providing a common language by which managers, planners, researchers, politicians, and citizen groups in all countries can exchange information and views.

P.H.C. (Bing) Lucas

Chair, IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected areas

At the IV World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, meeting in Caracas, Venezuela in February 1992, participants concluded that more and better managed protected areas were urgently required. Participants emphasised that protected areas are about meeting people's needs: that protected areas should not be islands in a sea of development but must be part of every country's strategy for sustainable management and the wise use of its natural resources, and must be set in a regional planning context.

The Caracas Congress also declared its belief in the importance of the full range of protected areas, from those that protect the world's great natural areas to those that contain modified landscapes of outstanding scenic and cultural importance. Within this broad spectrum of uses, many names have been applied to protected areas; Australia alone uses some 45 names and the US National Park Service has 18 different types of areas under its mandate. Globally, over 140 names have been applied to protected areas of various types. Bringing some order to this diversity is clearly a very useful step.

The purpose of these guidelines, therefore, is to establish greater understanding among all concerned about the different categories of protected areas. A central principle upon which the guidelines are based is that categories should be defined by the objectives of management, not by the title of the area nor by the effectiveness of management in meeting those objectives. The matter of management effectiveness certainly needs to be addressed, but it is not seen as an issue of categorisation.

The guidelines build on work done by IUCN in this field over the past of a quarter century. In particular, they draw on the efforts of a task force established in 1984. They reflect the outcome of a wide-ranging debate over the past few years among protected area managers from around the world, including discussion and review at a workshop in Caracas. The outcome of this workshop was that the Congress adopted a recommendation urging that the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas and the IUCN Council endorse a system of categories for protected areas according to management objectives and that the system be commended to governments and explained through guidelines. The present publication is designed to give effect to this particular recommendation.

It is hoped that these guidelines will be used widely by those planning to set up new protected areas, and by those reviewing existing ones. They are designed to form a useful basis for preparing national protected areas systems plans. It is to be emphasized that these categories must in no way be considered as a 'driving' mechanism for governments or organizations in deciding the purposes of potential protected areas. Protected areas should be established to meet objectives consistent with national, local or private goals and needs (or a mixture of these) and only then be labelled with an IUCN category according to the management objectives developed herein. These categories have been developed to facilitate communication and information, not to drive the system.

The guidelines do not stand alone, of course. Much other advice on the management of protected areas has been published by IUCN in recent years, and more is to come as the fruits of the work at Caracas emerge in print. But these guidelines have a special significance as they are intended for everyone professionally involved in protected areas, providing a common language by which managers, planners, researchers, politicians, and citizen groups in all countries can exchange information and views.

P.H.C. (Bing) Lucas

Chair, IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected areas

protected area management

INTRODUCTION

At the IV World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, meeting in Caracas, Venezuela in February 1992, participants concluded that more and better managed protected areas were urgently required. Participants emphasised that protected areas are about meeting people's needs: that protected areas should not be islands in a sea of development but must be part of every country's strategy for sustainable management and the wise use of its natural resources, and must be set in a regional planning context.

The Caracas Congress also declared its belief in the importance of the full range of protected areas, from those that protect the world's great natural areas to those that contain modified landscapes of outstanding scenic and cultural importance. Within this broad spectrum of uses, many names have been applied to protected areas; Australia alone uses some 45 names and the US National Park Service has 18 different types of areas under its mandate. Globally, over 140 names have been applied to protected areas of various types. Bringing some order to this diversity is clearly a very useful step.

The purpose of these guidelines, therefore, is to establish greater understanding among all concerned about the different categories of protected areas. A central principle upon which the guidelines are based is that categories should be defined by the objectives of management, not by the title of the area nor by the effectiveness of management in meeting those objectives. The matter of management effectiveness certainly needs to be addressed, but it is not seen as an issue of categorisation.

The guidelines build on work done by IUCN in this field over the past of a quarter century. In particular, they draw on the efforts of a task force established in 1984. They reflect the outcome of a wide-ranging debate over the past few years among protected area managers from around the world, including discussion and review at a workshop in Caracas. The outcome of this workshop was that the Congress adopted a recommendation urging that the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas and the IUCN Council endorse a system of categories for protected areas according to management objectives and that the system be commended to governments and explained through guidelines. The present publication is designed to give effect to this particular recommendation.

It is hoped that these guidelines will be used widely by those planning to set up new protected areas, and by those reviewing existing ones. They are designed to form a useful basis for preparing national protected areas systems plans. It is to be emphasized that these categories must in no way be considered as a 'driving' mechanism for governments or organizations in deciding the purposes of potential protected areas. Protected areas should be established to meet objectives consistent with national, local or private goals and needs (or a mixture of these) and only then be labelled with an IUCN category according to the management objectives developed herein. These categories have been developed to facilitate communication and information, not to drive the system.

The guidelines do not stand alone, of course. Much other advice on the management of protected areas has been published by IUCN in recent years, and more is to come as the fruits of the work at Caracas emerge in print. But these guidelines have a special significance as they are intended for everyone professionally involved in protected areas, providing a common language by which managers, planners, researchers, politicians, and citizen groups in all countries can exchange information and views.

P.H.C. (Bing) Lucas

Chair, IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected areas

At the IV World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, meeting in Caracas, Venezuela in February 1992, participants concluded that more and better managed protected areas were urgently required. Participants emphasised that protected areas are about meeting people's needs: that protected areas should not be islands in a sea of development but must be part of every country's strategy for sustainable management and the wise use of its natural resources, and must be set in a regional planning context.

The Caracas Congress also declared its belief in the importance of the full range of protected areas, from those that protect the world's great natural areas to those that contain modified landscapes of outstanding scenic and cultural importance. Within this broad spectrum of uses, many names have been applied to protected areas; Australia alone uses some 45 names and the US National Park Service has 18 different types of areas under its mandate. Globally, over 140 names have been applied to protected areas of various types. Bringing some order to this diversity is clearly a very useful step.

The purpose of these guidelines, therefore, is to establish greater understanding among all concerned about the different categories of protected areas. A central principle upon which the guidelines are based is that categories should be defined by the objectives of management, not by the title of the area nor by the effectiveness of management in meeting those objectives. The matter of management effectiveness certainly needs to be addressed, but it is not seen as an issue of categorisation.

The guidelines build on work done by IUCN in this field over the past of a quarter century. In particular, they draw on the efforts of a task force established in 1984. They reflect the outcome of a wide-ranging debate over the past few years among protected area managers from around the world, including discussion and review at a workshop in Caracas. The outcome of this workshop was that the Congress adopted a recommendation urging that the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas and the IUCN Council endorse a system of categories for protected areas according to management objectives and that the system be commended to governments and explained through guidelines. The present publication is designed to give effect to this particular recommendation.

It is hoped that these guidelines will be used widely by those planning to set up new protected areas, and by those reviewing existing ones. They are designed to form a useful basis for preparing national protected areas systems plans. It is to be emphasized that these categories must in no way be considered as a 'driving' mechanism for governments or organizations in deciding the purposes of potential protected areas. Protected areas should be established to meet objectives consistent with national, local or private goals and needs (or a mixture of these) and only then be labelled with an IUCN category according to the management objectives developed herein. These categories have been developed to facilitate communication and information, not to drive the system.

The guidelines do not stand alone, of course. Much other advice on the management of protected areas has been published by IUCN in recent years, and more is to come as the fruits of the work at Caracas emerge in print. But these guidelines have a special significance as they are intended for everyone professionally involved in protected areas, providing a common language by which managers, planners, researchers, politicians, and citizen groups in all countries can exchange information and views.

P.H.C. (Bing) Lucas

Chair, IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected areas

protected area management

Guidelines for Protected Area Management Categories

Background

Through its Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPPA), IUCN has given international guidance on the categorisation of protected areas for nearly a quarter of a century. The purposes of this advice have been:

to alert governments to the importance of protected areas;

to encourage governments to develop systems of protected areas with management aims tailored to national and local circumstances;

to reduce the confusion which has arisen from the adoption of many different terms to describe different kinds of protected areas;

to provide international standards to help global and regional accounting and comparisons between countries;

to provide a framework for the collection, handling and dissemination of data about protected areas; and

generally to improve communication and understanding between all those engaged in conservation.

As a first step, the General Assembly of IUCN defined the term 'national park' in 1969. Much pioneer work was done by Dr Ray Dasmann, from which emerged a preliminary categories system published by IUCN in 1973. In 1978, IUCN published the CNPPA report on Categories, Objectives and Criteria for Protected Areas, which was prepared by the CNPPA Committee on Criteria and Nomenclature chaired by Dr Kenton Miller. This proposed these ten categories:

I Scientific Reserve/Strict Nature Reserve

II National Park

III Natural Monument/Natural Landmark

IV Nature Conservation Reserve/Managed Nature Reserve/Wildlife Sanctuary

V Protected Landscape

VI Resource Reserve

VII Natural Biotic Area/Anthropological Reserve

VIII Multiple Use Management Area/Managed Resource Area

IX Biosphere Reserve

X World Heritage Site (natural)

This system of categories has been widely used. It has been incorporated in some national legislation, used in dialogue between the world's protected area managers, and has formed the organisational structure of the UN List of National Parks and Protected Areas (which in recent editions has covered Categories I-V).

Nonetheless, experience has shown that the 1978 categories system is in need of review and updating. The differences between certain categories are not always clear, and the treatment of marine conservation needs strengthening. Categories IX and X are not discrete management categories but international designations generally overlain on other categories. Some of the criteria have been found to be in need of a rather more flexible interpretation to meet the varying conditions around the world. Finally, the language used to describe some of the concepts underlying the categorisation needs updating, reflecting new understandings of the natural environment, and of human interactions with it, which have emerged over recent years.

In 1984, therefore, CNPPA set up a task force to review the categories system and revise it as necessary. This had to take account of several General Assembly decisions dealing with the interests of indigenous peoples, wilderness areas and protected landscapes and seascapes. The report of the task force, which was led by the then Chair of the CNPPA, Mr Harold Eidsvik, was presented to a CNPPA meeting at the time of the IUCN General Assembly in Perth, Australia, in November 1990. It proposed that the first five categories of the 1978 system should form the basis of an up-dated system; it also proposed the abandonment of categories VI-X.

The report was generally well received. It was referred to a wider review at the Fourth World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, at Caracas, Venezuela, February 1992. The Congress workshop to which the topic was assigned also had before it an analysis by IUCN consultant, Mr John Foster. Members of the workshop reviewed this material and recommended the early production of guidelines to replace those adopted in 1978. This was formally affirmed in Recommendation 17 of the Congress. Revised guidelines were then prepared and reviewed by the CNPPA Steering Committee and the IUCN Council in accordance with Recommendation 17. The result is these present guidelines, which incorporate general advice on protected area management categories (Part I), consider each of the categories in turn (Part II), and include a number of examples from around the world showing the application of the different categories (Part III).

These present guidelines, therefore, represent the culmination of an extensive process involving a wide-ranging review within the protected area constituency over a number of years. The opinions of those involved have been many. Some have recommended radical changes from the 1978 guidance; others no change whatsoever. Some have urged that there be regional versions of the guidelines; others that the categories be rigidly adhered to everywhere.

The conclusion is guidelines which:

adhere to the principles set forth in 1978 and reaffirmed in the task force report in 1990;

update the 1978 guidelines to reflect the experience gained over the years in operating the categories system;

retain the first five categories, while simplifying the terminology and layout;

add a new category;

recognise that the system must be sufficiently flexible to accommodate the complexities of the real world;

illustrate each of the six categories with a number of brief case studies to show how the categories are being applied around the world; and

provide a tool for management, not a restrictive prescription.

Background

Through its Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPPA), IUCN has given international guidance on the categorisation of protected areas for nearly a quarter of a century. The purposes of this advice have been:

to alert governments to the importance of protected areas;

to encourage governments to develop systems of protected areas with management aims tailored to national and local circumstances;

to reduce the confusion which has arisen from the adoption of many different terms to describe different kinds of protected areas;

to provide international standards to help global and regional accounting and comparisons between countries;

to provide a framework for the collection, handling and dissemination of data about protected areas; and

generally to improve communication and understanding between all those engaged in conservation.